As of 2020, scientists estimate a remaining cumulative emissions budget of 400 gigatonnes of greenhouse gases measured in carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e) to keep global average surface temperature within 1.5°C of preindustrial levels (Rogelj et al. 2019).[1]

Business-as-usual adds 40 GtCO2 to the atmosphere each year, using up our 1.5°C budget in 10 years. The budget estimated to correspond with a 2°C temperature rise is 1000 GtCO2, which is likely to have far more devastating consequences than already experienced at 1°C warming and at the 1.5°C warming we are hoping to keep within (IPCC (2018).

Annual emissions must reach net zero for the global climate to stop warming. If human activity can emulate natural carbon systems, removing more emissions from the atmosphere than we emit, we can begin to reverse this climate chaos. It takes time to reduce emissions. The UNEP Emissions Gap Report (2019) estimates that emissions reductions of at least 7.3% per year are required to keep warming within 1.5°C.

Comprehensive

modelling of climate solutions indicates the diversity avenues for emissions

reduction—from technological to behavioural—that are already available for

implementation and are economically viable. Models show that climate solutions

save more money than they cost (Hawken 2017).[2] Yet

these solutions are not going to be implemented fast enough by market forces—they

need to be facilitated and incentivised by the world’s leaders and governments.

These twelve proposals comprise my climate policy wishlist for Australia:

- Set

targets to halve annual emissions by 2030 and reach net zero emissions by 2040

- Re-focus

the economy on improving human and planetary wellbeing rather than GDP growth

- Transition

to net zero emissions energy sources

- Transition

to net zero emissions construction and buildings

- Transition

to net zero emissions manufacturing and consumption

- Transition

to net zero emissions transport

- Protect,

restore and manage of bushlands, forests, wildlife, biodiversity and ecosystems

- Transition

to sustainable agriculture and farming

- Family

planning programmes, empowerment of women and reduce inequality

- Incentivise

the market toward net zero- emission production and consumption e.g. carbon tax

- Use

Government contracts to incentivise shifts by giving preference to businesses

committed to net zero emissions targets

- Education,

research and implementation of the above and other climate solutions.

The overarching vision is of a transition to zero emission energy sources and electricity, transportation, agriculture, manufacturing, consumption and land use.

To secure

a sustainable future, decision-making at multiple levels must put the long-term

wellbeing of people and the planet, before short-term monetary gains. It is

pivotal that Government initiate, support and fund these changes.

Download Word file here for adaptation and submission to MPs.

1. Set targets to halve annual emissions by 2030 and reach net zero emissions by 2040

Australia

is a wealthy nation that can help lead the way to net zero emissions over the

next three decades. We want our Government to commit to at least 7.3% annual emissions

reductions across Australia’s production of direct emissions and consumption of

indirect emissions. This could see us halve Australia’s annual emissions from

2020 levels by 2030, and riding on this success reach net zero emissions by

2040. The Government can facilitate and incentivise these changes in our production

and consumption via the below suggestions.

2. Re-focus the economy on improving human and planetary wellbeing rather than GDP growth

GDP is a

measure of income and spending. The inadequacies of GDP have been acknowledged

since its initial design. GDP counts the bad as good (such as money spent on wars,

oil spills and treating illnesses); it ignores many goods (such as parents

caring for their own children and growing one’s own food); and assumes that GDP

increases are shared by the entire population (while not distinguishing to whom

the income and spending is distributed).[3]

Economic growth is not intrinsically good. GDP growth is good growth if

improves the wellbeing of people and the planet, and it is bad growth if it

does not. Following New Zealand and Bhutan’s example, we want our Government to

focus on a Happiness Index or Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI) rather than GDP.

We want national, state and local policies to be directed at the latter, aiming

to maximise wellbeing at minimal economic and environmental costs.

3. Transition to net zero emissions energy sources

One key

to a net zero emissions economy is the transition of energy sources from fossil

fuels to renewable, net zero emissions energy sources. We want our Government

to:

- transfer fossil fuel subsidies to renewable energy subsidies

- enable distributed “smart” power grids, such as networks of rooftop solar energy sharing where possible

- fund publicly-owned solar and wind farms, onshore or offshore, methane digesters, and energy storage

- cease putting public funding into outdated infrastructures such as building new coal plants

- fund the re-training of fossil fuel workers to attain jobs in net zero emissions energy and other jobs in the net zero emissions economy

- leave fossil fuel reserves left in the ground, prohibit the building of new coal mines.

If

existing fossil fuel reserves are mined, sold and burned, it will put 2,500

GtCO2e into the atmosphere (Berners-Lee 2011: 175), increasing temperatures to such an extent that it would

render all life on earth extinct. Therefore, countries and companies must be

content to leave their reserves in the ground. There may be a demand overseas

right now and continuing this export market may boost Australian tax income,

but this demand is short-lived as renewable energy becomes cheaper than fossil

fuels. We must put the long-term health of people and the planet before these

short-term profits. Australia is a decade behind other countries yet with our

sunshine and our ingenuity we can still be leaders in the new market for solar

energy and battery storage.

4. Transition to net zero emissions construction and buildings

We want

our Government to encourage the retrofitting of old buildings and to work with

construction companies and researchers so that new buildings can be net zero

emission both in the way they function and in the materials, technologies and

processes used in their construction and maintenance. This includes through

insulation, green roofs, smart glass, smart thermostats, alternative cement,

recycling, etc.

5. Transition to net zero emissions manufacturing and consumption

While

Australia does far less manufacturing than they used to (e.g. of white goods,

fashion, cars, toys, etc.), we want our Government to encourage zero emission

manufacturing (onshore and offshore) and reductions and changes in consumption,

promoting what some call “sustainable materialism.” This means considering the full

lifecycle of products, from the raw materials extracted from earth, to the

electricity used to manufacture and transport products, to emissions involved

in use and the after-life of the product (directing this toward re-use rather

than landfill). Possible policies include:

- outlaw built-in-obsolescence, incentivise the creation of long-lasting products that can be repaired rather than ending up in landfill (which wastes the emissions involved in the whole product lifecycle)

- fund new jobs and businesses in product parts and repair, and innovations that reuse and repurpose goods

- encourage thinking about and reporting on the whole product lifecycle from extraction of raw materials through the production process, use and after-life

- support innovations in recycling of plastic and metals

- support a shift to ecologically sustainable, long-lasting fashion, outlaw “fast fashion” and fabrics that put microplastic into the ocean when washed

- provide infrastructure and training comprehensive recycling and composting

- incentivise massive reductions in food waste at all stages of food production and consumption, including farms, households, restaurants and supermarkets

- support the cultural shift to plant-rich diets

- ban air-freighted food imports,[4] encourage locally-grown and self-grown produce

- work with waste management and landfill companies, as well as building demolition and citizens to educate, fund and incentivise proper handling of refrigerants especially after use, the problems with leakage etc.

- consider setting up an Ethical Manufacturing Agency of sorts that would fund guidelines, review and reporting of products imported to or made in Australia. This includes ensuring not only that organisations abide by the Modern Slavery Act but also that they meet basic sustainability requirements such as no built-in-obsolescence, design for repair (making parts readily available), and that they are working to align with net-zero emissions targets.

6. Transition to net zero emissions transport

We want our

Government to support a transformation of transport such that:

- encourage the availability of low-cost, net zero emission vehicles, e.g. by reducing import taxes, providing subsidies, etc.

- build the infrastructure for electric vehicles, with solar- and wind-powered recharge stations

- facilitate affordable, clean and easily-accessible mass transport, from improving the time and reducing prices of buses and trains to investing in electric high-speed rail (like in the Netherlands)

- facilitate innovations in net zero emission fuel for airplanes

- until this is achieved, encourage the reduction of carbon-intensive flights via a large flight tax, using this money to restore forests and fund other climate solutions.

7. Protect, restore and manage of bushlands, forests, wildlife, biodiversity and ecosystems

We want

our Government to fund jobs that protect, restore and manage Australia’s

bushlands, forests, wildlife, biodiversity and ecosystems. Australia’s

Indigenous peoples have managed these lands for millennia, and the Government

could seek their advice and employment in land management roles.

8. Transition to sustainable agriculture and farming

We want

our Government to collaborate with livestock and agricultural farmers in

developing net zero emissions agriculture. This includes:

- increasing use of trees including encouraging use of silvopastures (forest pastures), growing tropical stables rather than normal staples (for example, more bananas, avocados, breadfruit, and legumes, over wheat, corn, rice and pulses) and tree intercropping

- moving from extractive agrochemical industrial farming to regenerative agricultural practices, creating robust, complex communities of plants that have a higher carbon intake and healthier soil, reducing the need for pesticides and chemical fertilizers

This

involves education, investment, changing business practice and changing

cultures and food practices.

9. Family planning programmes, empowerment of women and reduce inequality

Stabilising

humanity’s population growth is a pivotal element in reducing annual emissions.

We can help by supporting programmes that empower women, educate girls, and

alleviate poverty. This includes:

- community-led family planning programmes

- community-led education programmes

- structural changes that enable greater equality within and between countries (e.g. relieve debt burdens, encourage self-sufficiency over cash cropping, etc.)

- fund businesses working in local contexts with low-income people to improve cookstoves and support women smallholders.

10. Incentivise the market toward zero- emission production and consumption e.g. carbon tax

We want

our Government to help mobilise a sustainable economy through market mechanisms

such as a carbon tax, anti-trust laws and reducing inequality for a better

functioning democracy. A carbon tax of US$70/tCO2 can reduce

emissions by 10-40% in different countries (UNEP 2018: xxii).

Leading scholars recommend a carbon tax of US$50/tCO2, with a plan

to steadily increase it to US$400/tCO2 (Rockström et al. 2017). The

business community welcomes the market predictability this would provide. Anti-trust

law prevents monopolies, such as those we have allowed in our media. It is the

role of Government to prevent monopolies as a basic condition for market

economies to function. Inequality feeds a cycle of wealth-power-wealth and

erodes democracy. Reducing inequality and seeking “complex equality” is one way

to enable your own democratically-led decision-making.

11. Use Government contracts to incentivise shifts by giving preference to businesses committed to net zero emissions targets

We want

our Government to use their contracts to shift the focus of businesses to

long-term human and nonhuman wellbeing over short-term monetary gains.

12. Education, research and implementation of the above and other climate solutions.

We want

our Government to increase funding for research and implementation of climate

solutions. This includes:

- carbon sequestration that works

with natural processes (e.g. biochar)

- careful and holistic approaches

to geoengineering

- education programs for citizen

and businesses on high impact avenues for emissions reductions (from LED

lighting to water saving, household recycling, buying less, ridesharing,

insulating houses, reducing use of heating/cooling, taking less flights,

driving less or living car-free, using recycled paper at home and work, investing

in rooftop solar, etc.)

- all other climate solutions.

References:

Berners-Lee, Mike, How

Bad Are Bananas? The Carbon Footprint of Everything, Vancouver, Greystone

Books, 2011.

Chancel, Lucas

and Thomas Piketty. Carbon and

Inequality: from Kyoto to Paris. Paris: Paris School of Economics, 2015.

Hawken, Paul, Drawdown: the most comprehensive plan ever

proposed to reverse global warming, New York, Penguin, 2017.

IPCC. Global Warming of 1.5 °C: An IPCC Special

Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels

and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of

strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable

development, and efforts to eradicate poverty. United Nations International

Panel on Climate Change, 2018.

Kubiszewski,

Ida, Robert Costanza, Carol Franco, Philip Lawn, John Talberth, Tim Jackson and

Camille Aylmer, “Beyond GDP: Measuring and achieving global genuine progress”, Ecological Economics, 93, (2013), 57-68.

Raworth, Kate, Doughnut economics: seven ways to think like

a 21st-century economist, London, Random House Business Books, 2017.

Rockström,

Johan, Owen Gaffney, Joeri Rogelj, Malte Meinshausen, Nebojsa Nakicenovic and

Hans Schellnhuber, “A Roadmap for Rapid Decarbonization”, Science, 355, 6331, (2017), 1269-71.

Rogelj, Joeri,

Piers M. Forster, Elmar Kriegler, Christopher J. Smith and Roland Séférian,

“Estimating and tracking the remaining carbon budget for stringent climate

targets”, Nature, 571, (2019),

335-42.

UNEP. The Emissions Gap Report 2018. Nairobi:

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), 2018.

——. Emissions Gap Report 2019. Nairobi:

United Nations Environment Programme, 2019.

[1] These estimates, are in the 50-66% probability range, are adjusted

for 2018 and 2019, and they include a provision of 100 GtCO2

projected to be released by melting permafrost.

[2] The total spending involved in implementing the top 80 solutions is

estimated at $29,609 billion, while the total savings are $74,362 billion—this

is to say, these solutions incur a net

saving of $44,753 billion over the period 2020-30. Also see Project

Drawdown’s website: https://www.drawdown.org

[3] For more on this see Kubiszewski et al. 2013; Raworth 2017.

[4] Shipping is 100 times more carbon efficient than air-freight, yet

locally-grown, seasonal foods are even better (Berners-Lee 2011: 83).

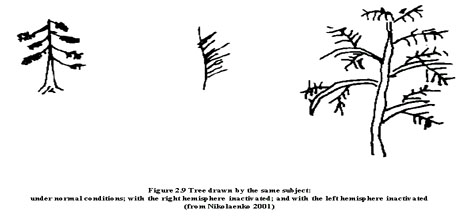

Recent work in neuroscience, for example on stroke survivors and using new technologies that light up when different parts of the brain are being used, are illuminating this in exciting ways.

Recent work in neuroscience, for example on stroke survivors and using new technologies that light up when different parts of the brain are being used, are illuminating this in exciting ways. First it is important to make clear, as McGilchrist does again and again that the idea that the left hemisphere gives us reason and language, while the right hemisphere gives us images and emotion is false: we need both hemispheres in order to deal with these things, from reason and emotions to interpreting language and images. McGilchrist writes: ‘every identifiable human activity is actually served at some level by both hemispheres’ (1).

First it is important to make clear, as McGilchrist does again and again that the idea that the left hemisphere gives us reason and language, while the right hemisphere gives us images and emotion is false: we need both hemispheres in order to deal with these things, from reason and emotions to interpreting language and images. McGilchrist writes: ‘every identifiable human activity is actually served at some level by both hemispheres’ (1). In this RSA 21st Century Enlightenment animation to McG’s TED Talk you can get a good introduction to these ideas:

In this RSA 21st Century Enlightenment animation to McG’s TED Talk you can get a good introduction to these ideas:

My latest academic publication – on the work of my favourite philosopher of all time: Alan Watts, and how his “dramatic model of the universe” can contribute to peace 🙂

My latest academic publication – on the work of my favourite philosopher of all time: Alan Watts, and how his “dramatic model of the universe” can contribute to peace 🙂