I knew I would leave India with a new perspective of life – but the upturning of my worldview has happened in a far different way than I expected. I thought I would arrive home more passionate about social justice, more inspired to make a difference to the lives of “poor” people. Instead I am leaving India with a hardened heart, more humility, and an increased concern for the future of humanity as a whole. Why? Because the population problem, the elephant in the room, is far too big a problem to ignore. And I simply cannot see a solution to this problem.

I knew I would leave India with a new perspective of life – but the upturning of my worldview has happened in a far different way than I expected. I thought I would arrive home more passionate about social justice, more inspired to make a difference to the lives of “poor” people. Instead I am leaving India with a hardened heart, more humility, and an increased concern for the future of humanity as a whole. Why? Because the population problem, the elephant in the room, is far too big a problem to ignore. And I simply cannot see a solution to this problem.

Before I went to India, as those of you who have read older blog entries would know, I quite idealistically analysed the global inequalities and blamed war and poverty on western greed.

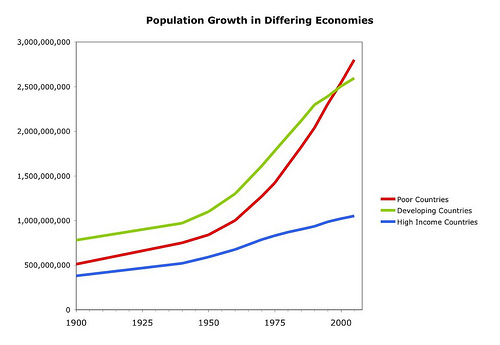

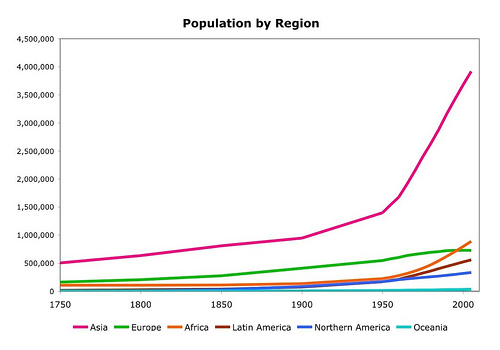

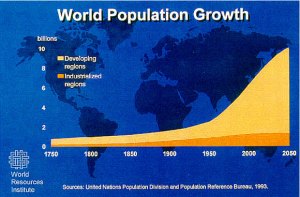

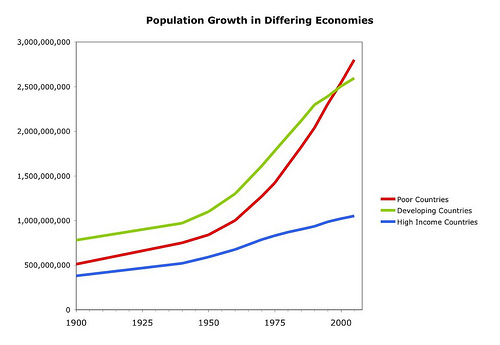

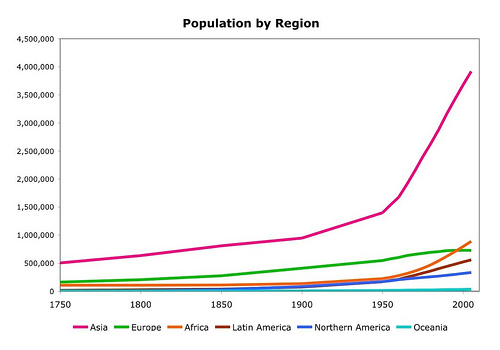

I looked at these graphs of population growth by economy and region, and blamed the population growth on western development.

Why does the population of poor and developing countries suddenly increase in 1940s, and high income countries only increase a little?

Why does the population of poor and developing countries suddenly increase in 1940s, and high income countries only increase a little?

What is going on in Asia???

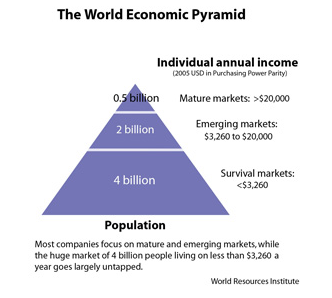

In my mind, the population had increased so much since WW2 simply because of the design of the global capitalist system. Post-development scholars criticise the global system for being miperialistically geared to benefit the rich at the expense of the poor, with the raw materials bought for nothing and sold for billions and so making the rich richer and the poor poorer. I went a step further. It made sense to me that a larger population in developing countries equates to cheap labour, which means cheaper computers, phones, TVs, clothes, cars, chocolate etc. For a government subject at uni I analysed the power-distribution of the system, observing that it is the rich and powerful capitalists who pull the strings behind governments, the World Trade Organisation, the IMF, and other peak bodies. The rich and powerful capitalists I equated to anyone whose lives are not run by debt – those who have shares in companies, money in the bank, superannuation funds, own property without mortgages, own their own business etc. In particular it was the wealthiest of the wealthy – the people who own the banks themselves.

I thought education was the solution. Not education of the poor people, but education of the rich. I thought that if each of us understood the connection between our shopping habits and the mass workers, the connection between our consumption and our future environment, and that the roots of these to problems lay in the capitalist dream: to accumulate more money, then we would begin to move toward a more socially just and environmentally sustainable system.

I thought that the motivation to change our systems would come from a “new dream” that started with rediscovering the connection with our planet, so that we each come to prioritise the whole ecosystem that we are a part of, over and above our individual selfish desires. I thought that this would come from an understanding of Big History, coming to identify ourselves as part of the process of our Universe expanding and increasing in complexity (or what many, including myself, personify as “God”) .

Now, well, now I realize that the answers to the world’s problems are not that simple. There are far deeper roots to this systematic problem than western greed. It seems to me, in this moment in time, that the global system is NOT a simple cause and effect situation with western greed causing global poverty.

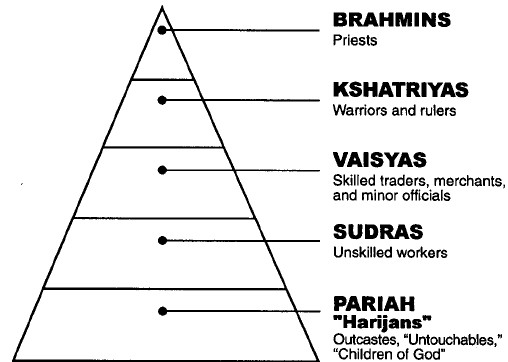

For one, inequality is not just a problem in today’s global system, it has always been a problem. Secondly, inequality’s root problem – greed – is not a western problem but is a human problem, a life problem. Thirdly, poverty has cultural, religious and historical roots that have nothing to do with the global system. The caste system existed in India before the British arrived. The caste system is thousands of years old and while Gandhi may have officially abolished it, culture is stronger than law. In India this caste system keeps poor poor and the rich rich, and this has nothing whatsoever to do with global capitalism.

Capitalists may benefit from the fact that China and India are over-populated, and hence human labour is cheap, but capitalists are not standing over these people telling them to have more babies.

Sure there’s the tiny motivational factor of more children equals more money, but talking to Indians at different income levels it seemed to be the cultural aspects (tradition, the values placed on family, lack of entertainment etc) that are behind the population explosion over and above their desire to make money from them. If women get married at 10 and have babies the rest of their life, for cultural reasons over and above any monetary motivation, how can poverty ever be addressed? It is their own actions which perpetuate their poverty and cause the inequalities of the global system to continue.

Should capitalists stop benefiting from cheap labour? That would only mean these people have less job opportunities… that’s not going to help. What if they pay them a little extra, that is, change to a “fair trade” system? This may help a few lives but when people are willing to work for less, because working for less is better than working for nothing, how can such a “fair” system be sustained? How is it “fair” if some people have jobs paying fair wages, while the rest of the billions have no job at all?

Fair trade or free trade, escaping poverty is a choice that people in the situation will collectively have to make for themselves. And unfortunately eradicating poverty requires doing something about that frickin big elephant staring everyone in the face. What? I have NO IDEA. Could this be why so many yogis and religious leaders advise to withdraw from the world and look for peace inside?

And so my worldview crisis…

As a result of the fear that comes from this lack of solutions, the altruistic side that used to dominate my mind is becoming more self-centered: what future do I want for the future generations that spring from the people I love? My previous almost disdain for wealth, thinking all money was intrinsically connected to a corrupt system, is turning into an appreciation of it. Work hard, work smart, then share and enjoy your earnings with your family and friends… what’s so bad about that?

Let’s face it, animal, plant, or human; black, white or in between; this is ultimately life’s instinctive purpose: to live as long as we can, and create offspring to continue our work when we die. That’s why we choose the partners we choose to mate with. That’s why we fight the wars we fight. That’s why we work so hard to buy a house and establish systems of governance, education and business. SELF-PRESERVATION and PROCREATION.

India has given me a new appreciation for the work my ancestors – for their efforts to create a world so good for us, their children. Maybe their methods weren’t so peaceful, with inquisitions, colonialism and imperialism, but let’s face it: it’s not only our ancestors who have done this and if it wasn’t them, it would have been someone else. Before the British invaded India, it was the Moghuls, and before that it was other nations from Central Asia. The British were far from the first, and it is highly unlikely they will be the last.

My experiences in India have left me thinking that if the wealthy of the world did suddenly decide to spread their wealth, to educate the billions in poverty and create a socially-just system; the peace it would create would probably be short-lived and soon all the densely populated places like India would spread to populate the rest of the world. My favourite city would become just like my least favourite, and so would every other city in the world.

I realise my perspective is becoming incredibly selfish, but I do not want people sleeping and dying on our streets; I do not want people trying to rip me off on street corners; I do not want to be living in a dirty, polluted, noisy, over-populated place. In short, I do not want to see Sydney turn into Mumbai.

According to http://www.overpopulation.org/ if we continue at our present rates, our population will be over 11 billion by 2035!!! And what then, will Australia still be sitting there with it’s 21 million people? I don’t think so. With Australia’s rivers drying up there just ain’t enough water for everyone. Nor infrastructure, or systems for food, housing, anything…

And so I worry, might my passionate pursuits to make a more socially just world bring the extinction of my own culture, my country’s wealth and the life style, and all the opportunities our ancestors dedicated their lives to deliver?

While our own culture is no where near perfect, with its insatiable desires and materialistic emptiness, western culture has A LOT to offer: freedom; the scientific quest for knowledge; the creativity that comes from competition; the opportunities for individualistic pursuits. It would be a big shame to lose it in place of an overpopulated communistic uncreative mess.

Think about it, if income was distributed evenly, will the 2 billion women of child-bearing age suddenly decide not to have babies? And, if the wealthy were to even out the income, my new lack-of-faith-in-humanity makes it seem realistic to assume that another group of people would rise up and the same cycles of violence would begin just with a new group of rich and powerful. And, even if this didn’t happen, how long would it take before we would run out of resources (seeing as ecological economists say 10 planets would be required for all people of the world to live an American lifestyle)? Does this mean, simply in attempt to better the lives of people with less money today, all of humanity will die out? I’m sorry, but I don’t think this would be good for anyone involved.

Okay, okay, calm down Juliet, calm down. As you can see there is a lot going through my head. Out of fear I’m becoming defensive. I’m guess I’m still culture-shocked, and struggling to comprehend the reality of our global situation. It’s one thing to see population in a graph but it’s a different kettle of fish to see it with your own eyes. When one’s mind connects such a mess to projections of possible futures for earth and humanity it’s really quite a confusing and scary topic.

Damned if you do, damned if you don’t:

- If you consider population control then what about human rights?

- If you don’t control the population then what do you do about the billions living in poverty?

- If you bring people out of poverty then you destroy the planet for everyone.

Now I understand why overpopulation has been the elephant in the room that no one wants to talk about.

My conclusion: “Elephant? What elephant??? I don’t see it either!”

…

Follow up thoughts six years later… February 2016

I received a comment that drew my attention back to this post and I thought I should revisit the “elephant in the room” in light of some things that I have learned since 2010, and some things that have changed in the world during this time.

I deleted a paragraph that a commenter interpreted as bordering on racism. It’s difficult: one’s views can be taken out of context and considered unchanging, so what if someone looks at that and starts thinking I’m racist? That being said I think everyone is “a little bit racist”, in some ways, and we go overboard trying to be politically correct – sometimes at the cost of honesty, and being able to speak one’s mind.

I value difference – I value different cultures and peoples, and I think it is important to avoid imperialism, and other forces, taking away from our beautiful diversity – unless in the opportunity for self-determination people choose to change and evolve in ways they want to change, integrating parts of other cultures. It is just as dangerous to romanticise a culture and group of people, and want them to stay the same, as it is to attempt to interfere and change them. A people should be able to choose for themselves how their culture evolves.

Australia has and is committing devastating human rights abuses against people seeking help from and refuge in our country, and I do not in any way condone this. Hence my deleting a paragraph that may have been interpreted as supporting Australia’s immigration policies. I don’t. I think the White Australia Policy was shocking, as has been every In the context of someone in their twenties having a rant it was not racist, but as something that might be attributed to me later in life, not so good.

In my mind at that time, battling with the confronting nature of my own experiences in the chaotic suburbs of Mumbai in contrast to the affluent bubble of Sydney, I saw some of the need for a strict immigration policy. My current opinion is that it is important to have a smart and humane immigration policy – one that sees the value in each person’s life, and works creatively to find space for them in the many parts of our country that are crying out for higher populations. And one that is linked ot foreign aid and international relations policies, helping to remedy past and current wrongs of Western civilisation that are at root of many wars and problems in the countries people have fled.

There are three messages that I want to add on to this blog entry:

- With regard to insights into India’s population – I learned a great deal on this from Vandana Shiva on her visit to Sydney in 2014. It had continued to puzzle me why India’s population increased so dramatically when it did. Dr Shiva attributes this to colonialism and the removing of peasants from land, which created uncertainty and instability, which led to people having more children.

- Furthermore Dr Shiva taught me that the caste system was not in the same negative form that one might interpret it today – Dr Shiva believes this has been reinterpreted by the West in a negative light, where it used to be more about division of roles and labour than hierarchy. It was a structure for society that worked, made sense.

- Possibilities for stabilising global population, lifting everyone out of poverty and living in harmony with our planet do exist, and all three must go together. We, especially those with the money and positions to do so, need to invest and support investment by our governments into çradle-to-cradle design and renewable energy technologies that offer ways in which humanity can live without destroying the planet. We also need to build support for various structural changes and restrictions e.g. on how much corporations can pollute, who pays for pollution and wastes, etc. If we can learn to live in ways that do not destroy the earth, then perhaps a large human population isn’t such a problem.

I’d like to add a final note about the changing nature of opinions. My views are constantly changing, and I hope that anything read on this blog can be understood in context that it was written by a person growing up, learning, and wanting to discuss different views and perspectives – all which I see as constantly changing through such a dialogical process.

I see the world in a very different way to what I did six years ago, particularly at this point in time where I’d found India so confronting. I leave this blog entry up here as I believe the process of changing our views, of thinking through the hard questions, of having a rant about contending ideas, is a valuable part of conversations necessary for addressing such problems and moving toward more ecological and peaceful futures.

So please do not judge me by the post above, but please use it as food for thought, for better understanding your own positions, which are too also likely to be developing and changing through time as the context for your ideas and expanding sphere of learning and influence also changes. Thank you!

Picture credits:

The Elephant in the Room – my own attempt at photoshopping a photo of an elephant from Taronga Zoo into my Opa’s sunroom.

Population graphs – wiki-commons

Good links found here – http://www.athropolis.com/links/pop.htm

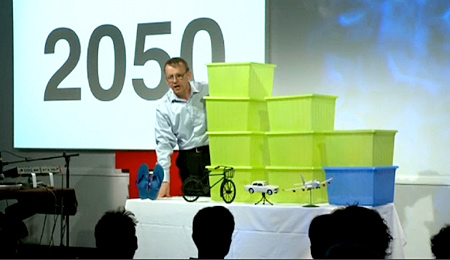

Only 2 more boxes, 2 billion more people, bringing us up to a grand total of 9 billion. And I guess ideally, eventually, all those boxes are stacked on top of one another at the far right, enjoying their holidays all around the world.

Only 2 more boxes, 2 billion more people, bringing us up to a grand total of 9 billion. And I guess ideally, eventually, all those boxes are stacked on top of one another at the far right, enjoying their holidays all around the world. Content in living out your life: work, money, weekends, holidays, home, kids… and then something happens: a cataclysmic event changes everything.

Content in living out your life: work, money, weekends, holidays, home, kids… and then something happens: a cataclysmic event changes everything.

To the Hindu caste system:

To the Hindu caste system:

I knew I would leave India with a new perspective of life – but the upturning of my worldview has happened in a far different way than I expected. I thought I would arrive home more passionate about social justice, more inspired to make a difference to the lives of “poor” people. Instead I am leaving India with a hardened heart, more humility, and an increased concern for the future of humanity as a whole. Why? Because the population problem, the elephant in the room, is far too big a problem to ignore. And I simply cannot see a solution to this problem.

I knew I would leave India with a new perspective of life – but the upturning of my worldview has happened in a far different way than I expected. I thought I would arrive home more passionate about social justice, more inspired to make a difference to the lives of “poor” people. Instead I am leaving India with a hardened heart, more humility, and an increased concern for the future of humanity as a whole. Why? Because the population problem, the elephant in the room, is far too big a problem to ignore. And I simply cannot see a solution to this problem.

So yesterday I enjoyed a little rant about the game our governments, supported by the people’s consumer-driven values, are playing with military pawns, strategically placed towers, and other oil-powered weaponry. We established the difficulty in knowing what sources we can trust, but decided that either way whatever moral and immoral tactics the governments are using with their present day “war of wants”, it is the westerners that gain the lifestyle benefits of cheap clothes and food and transport and travel. I am absolutely a beneficiary of this, and I must say I’m glad to be on my side of the fence. But we also established that our state of being is temporary. One day, if we keep playing this zero-sum game, someone else will be the winner and we will be the losers. I left you with a hint of hope: is there another way?

So yesterday I enjoyed a little rant about the game our governments, supported by the people’s consumer-driven values, are playing with military pawns, strategically placed towers, and other oil-powered weaponry. We established the difficulty in knowing what sources we can trust, but decided that either way whatever moral and immoral tactics the governments are using with their present day “war of wants”, it is the westerners that gain the lifestyle benefits of cheap clothes and food and transport and travel. I am absolutely a beneficiary of this, and I must say I’m glad to be on my side of the fence. But we also established that our state of being is temporary. One day, if we keep playing this zero-sum game, someone else will be the winner and we will be the losers. I left you with a hint of hope: is there another way?