“Your skin doesn’t separate you from the world; it’s a bridge through which the external world flows into you, and you flow into it.”

More Alan Watts? Yes, it’s always a good time for more Alan Watts. Over and over and over, repeat.

“The whole world is moving through you, all the cosmic rays, all the food you’re eating, the stream of steaks and milk and eggs and everything is just flowing right through you.”

Have you ever thought about your self in this way? In goes oxygen, water, sunshine and food. Out goes carbon dioxide, piss and shit. We all know that our bodies are is constantly in-taking and expelling the world, but I’m not sure many of us feel ourselves as fully connected and inseparable from our environment.

What ways, then, can we define ourselves as separate from and connected to our environment?

Watts likens us to a whirlpool in water:

“you could say because you have a skin you have a definite shape you have a definite form. All right? Here is a flow of water, and suddenly it does a whirlpool, and it goes on. The whirlpool is a definite form, but no water stays put in it. The whirlpool is something the stream is doing, and exactly the same way, the whole universe is doing each one of us, and I see each one of you today and I recognize you tomorrow, just as I would recognize a whirlpool in a stream. I’d say ‘Oh yes, I’ve seen that whirlpool before, it’s just near so-and-so’s house on the edge of the river, and it’s always there.’ So in the same way when I meet you tomorrow, I recognize you, you’re the same whirlpool you were yesterday. But you’re moving…. When you’re wiggling the same way, the world is wiggling, the stream is wiggling you.”

Why do we tend to think of ourselves as separate from our environment? Why do we wage wars on nature, when we are in fact a part of nature?

“the problem is,” explains Watts, “we haven’t been taught to feel that way. The myths underlying our culture and underlying our common sense have not taught us to feel identical with the universe, but only parts of it, only in it, only confronting it–aliens. And we are, I think, quite urgently in need of coming to feel that we ARE the eternal universe, each one of us… Otherwise we’re going to go out of our heads. We’re going to commit suicide, collectively, courtesy of H-bombs. And, all right, supposing we do, well that will be that, then there will be life making experiments on other galaxies. Maybe they’ll find a better game.”

Do we need a new religion? Watts says: No.

‘This, as history has shown repeatedly, is not enough. Religions are divisive and quarrelsome. They are a form of one-upmanship because they depend upon separating the “saved” from the “damned,” the true believers from the heretics, the in-group from the out-group… As systems of doctrine, symbolism, and behavior, religions harden into institutions that must command loyalty, be defended and kept “pure,” and – because all belief is fervent hope, and thus a cover-up for doubt and uncertainty – religions must make converts.’

What, then do we need?

“We do not need a new religion or a new bible. We need a new experience – a new feeling of what it is to be “I”.’

We need to deepen our understanding of our selves and our world, and expand our philosophy for life in ways that align with this understanding.

What does it feel like when one defines themselves as the universe?

1. it changes the feeling I have toward you

“I see every one of you as the primordial energy of the universe coming on at me in this particular way. I know I’m that, too.”

In this way I an inclined to enjoy your successes (as they are my successes too) and to feel your pain (as it is my pain too). This radical empathy brings me to point (2).

2. it increases care for the future of our species and our planet

‘When you know for sure that your separate ego is a fiction, you actually feel yourself as the whole process and pattern of life. Experience and experiencer become one experiencing, known and knowing one knowing.’

If I am the whole universe, I care about the creative possibilities and the destructive suffering of all the beings within that universe. What is best for all is what is best for myself, and I work to align my own actions to bring about the best for others.

3. it takes away loneliness—as I know that my roots connect me to all.

“We do not ‘come into’ this world; we come out of it, as leaves from a tree. As the ocean ‘waves,’ the universe ‘peoples.'”

4. it gives my life meaning and purpose.

Watts asks, “Why go on? And you only go on if the game is worth the gamble… a satisfactory theory of the universe has to be one that’s worth betting on.”

And (again) my favourite quote from Watts:

“You have seen that the universe is at root a magical illusion and a fabulous game, and that there is no separate ‘you’ to get something out of it, as if life were a bank to be robbed. The only real ‘you’ is the one that comes and goes, manifests and withdraws itself eternally in and as every conscious being. For “you” is the universe looking at itself from billions of points of view, points that come and go so that the vision is forever new.”

I find my meaning not in what I can take from others, for my individual body, but in what I can give to others and what I can give to the world as a whole. And I do this with the most selfish intention: giving, in my experience, is far more rewarding than taking.

We are each the narrator of our own life stories.

We can narrate ourselves as separate individuals, out to take from the world what we feel it owes us—we can set out to compete, beat and survive.

Or we can narrate ourselves as interconnecting processes, here to give to the world, to inspire the best in others and live on through the surrounding processes that we continue within when our own body dies.

The latter focalisation leads to greater happiness and satisfaction in the life that I’m living. For me, Alan Watt’s theory of the universe is one worth betting on.

Quotes are from various Alan Watts books and talks, largely The Book : On the Taboo against Knowing Who You Are (London: Jonathan Cape, 1969). pp. 15-8; and The Nature of Consciousness Watts (1960).

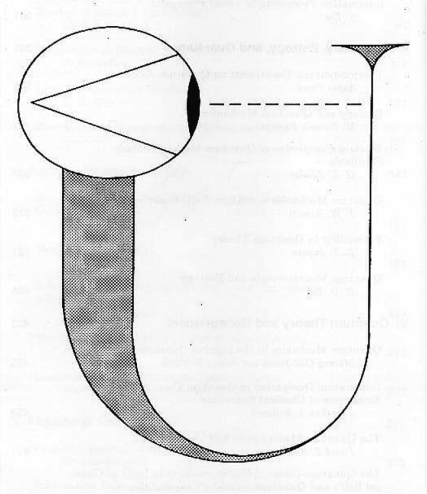

Picture is John Wheeler’s “Participatory Universe”, included in Paul Davies’ The Mind of God (1992: 225). Here we are represented as a self-reflexive eye that emerged within life’s story.

My latest academic publication – on the work of my favourite philosopher of all time: Alan Watts, and how his “dramatic model of the universe” can contribute to peace 🙂

My latest academic publication – on the work of my favourite philosopher of all time: Alan Watts, and how his “dramatic model of the universe” can contribute to peace 🙂

This book shares the same essential message of countless books, articles and lectures that followed: you are not only what is inside your “bag of skin”, you are what is outside of it too. To kick off the new year, let me explain what this means and how it relates to happiness…

This book shares the same essential message of countless books, articles and lectures that followed: you are not only what is inside your “bag of skin”, you are what is outside of it too. To kick off the new year, let me explain what this means and how it relates to happiness…

‘Extensive studies of colour perception over several decades have made it clear that there are no colours in the external world, independent of the process of perception.’

‘Extensive studies of colour perception over several decades have made it clear that there are no colours in the external world, independent of the process of perception.’