Chomsky and Foucault are two foundational modern and postmodern figures in the critique of “structures” of our society – from language to government to institutions – and analyzing whose has the “agency” to maintain or change these structures.

This is a debate between the two thinkers, who have very different ideas about structure and agency, and about the ideas of peace, justice, and oppression.

Part 1

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WveI_vgmPz8[/youtube]

Part 2

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=S0SaqrxgJvw[/youtube]

Chomsky has what is thought of as a “Modernist” or “Structuralist” perspective, holding that there is some common human objective and absolute definition of justice, goodness, and kindness.

Foucault on the other hand is thought of as more “Postmodernist” or “Poststructuralist”, believing that these definitions are always and entirely relative.

Knowledge from a postmodernist point of view is completely (might we cheekily say, “absolutely”) inseparable from the oppressive structures so that our definitions of peace and justice are in fact part of the oppressive structure and play a role in maintaining them.

Who is right, who is wrong?

Is, as Foucault argues, the “very notion of justice itself functions within a society of classes as a claim made by the oppressed class and as a justification for it”?

Or is there, as Chomsky defends, some kind of inner absolute notion that we may not be able to properly define, and yet that we all somehow share?

It’s a debate that has been going for millennium. Most of us have a modern or postmodern worldview – or some kind of mix of the two.

It’s a question of one Truth or many truths.

Some of us are likely to be on one end of the continuum upholding the idea of an objective truth (and hence some kind of objective definitions of peace and justice), while others might hold that all truth is relative (and hence our definitions of peace and justice are also relative).

I personally think the middle ground isn’t navigated enough, although I feel Chomsky in this clip is trying to get to it.

On one hand, like Foucault has emphasised, our entire way of thinking is based on our education and societal experiences. All our ideas, including that of peace and justice, are completely inseparable from these structures. Science, Philosophy, Religion and Culture – all our ideas and stories can be traced back to the beginnings of our recorded history, back to the “Ancient” cultures of Sumer, Egypt, Babylon and Greece. Everything that we know or think has a long “ancient” history of their own.

Our experience of reality is entirely socially constructed, and entirely relative.

And as Foucault points out, most of this construction has been designed by power-hungry beings, greedy, hierarchical, and tailoring “knowledge” and definitions of “justice” or what is “normal” and “good” for their own benefit.

But does that mean we should throw our hands in the air and forget about peace and justice? On this point I agree with Chomsky.

I think after we acknowledge our definitions are relative and based on partial knowledge, we can’t escape our own embodiment to this structure and hence we need to work within it toward some kind of vision of future.

There seems to be some common and objective Reality that we all share, and experienced via our own unique reality. We will never share the same experience of that Reality, so we can only ever know a relative version of it.

The more capacity we have to critically reflect on our views, and their historical and cultural context, the more likely we can learn from the past and create a better future.

So, in conclusion, I think Chomsky and Foucault make points that work together like yin and yang: we need to hold some definition of peace and justice as tentative, acknowledging its relative limitations. We need to strive toward our ideals while never stopping to question, discuss and revise their meanings.

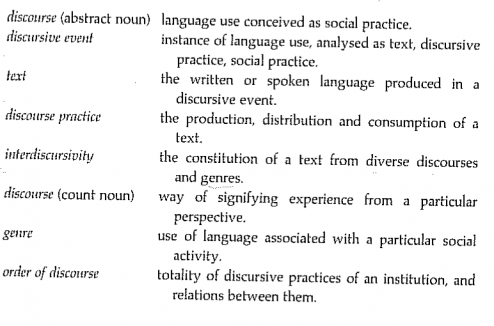

Critical Discourse Analysis is a study of LANGUAGE, IDEOLOGY, POWER and SOCIAL CHANGE. ‘Discourse analysis is not a “level” of analysis as, say, phonology or lexico-grammar, but an exploration of how “texts” at all levels work within sociocultural practices,’ says Candlin in the Preface to Fairclough. If you didn’t already gauge from the title then take this as your warning: this entry contains high levels of academic language. It is also disjointed and includes a lot of quotes (because I’m lazy).

Critical Discourse Analysis is a study of LANGUAGE, IDEOLOGY, POWER and SOCIAL CHANGE. ‘Discourse analysis is not a “level” of analysis as, say, phonology or lexico-grammar, but an exploration of how “texts” at all levels work within sociocultural practices,’ says Candlin in the Preface to Fairclough. If you didn’t already gauge from the title then take this as your warning: this entry contains high levels of academic language. It is also disjointed and includes a lot of quotes (because I’m lazy).

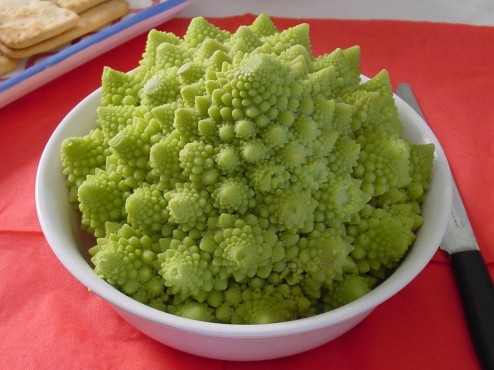

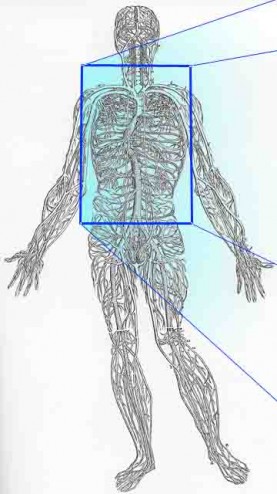

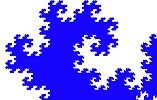

When I inside and outside my “self”, I see one thing: fractals. Fractals explain to me the microcosm and the macrocosm that our cells, bodies, societies, galaxies, and possibly universes and beyond, are a part of.

When I inside and outside my “self”, I see one thing: fractals. Fractals explain to me the microcosm and the macrocosm that our cells, bodies, societies, galaxies, and possibly universes and beyond, are a part of. A fractal is a shape that you can split into parts, zoom in, and discover the same or similar shape, times infinity. It’s almost magic, this pattern which extends outward and inward, seemingly to infinity. I’ll use the Koch Snowflake among others examples of fractals to introduce what I find a very exciting concept it to you.

A fractal is a shape that you can split into parts, zoom in, and discover the same or similar shape, times infinity. It’s almost magic, this pattern which extends outward and inward, seemingly to infinity. I’ll use the Koch Snowflake among others examples of fractals to introduce what I find a very exciting concept it to you.

Closer look at lightning

Closer look at lightning

[9]

[9] [10]

[10]