“The day came when the risk to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom” —Anais Nin

Throughout my yoga class on Wednesday my teacher repeated the quote: “The day came when the risk to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom”…

Yoga is not about stretching and fitness, although these are nice side effects. Yoga is about opening the body, the mind and the spirit—but most of all it is about connection.

The Sanskrit word yoga literally means “to join” or “to unite”. Yoga cultivates mental peace and physical health, but its most essential aim is to bring about a ‘union with the Divine Reality of our being’ (Aurobindo 1996: 280).

Yoga is the process of ‘union of the human individual with the universal and transcendent Existence we see partially expressed in man [sic] and in the Cosmos’ (6).[1]

In my experience, yoga offers a source of inner peace—well-being and mental clarity. Yoga also offers a source of hope for bringing about a more socially just and ecologically sustainable global society—as it works to align one’s own interests with the long-term interests of the Earth community.

Yoga and its principles teach of simple being and living simply, centring the self and reflecting on one’s place in space and time. The opening up of the body, the opening up of the spirit, the opening up of the mind, encourages a letting go of fear and an understanding that you are inseparable from your environment. We are a part of nature, not masters of it.

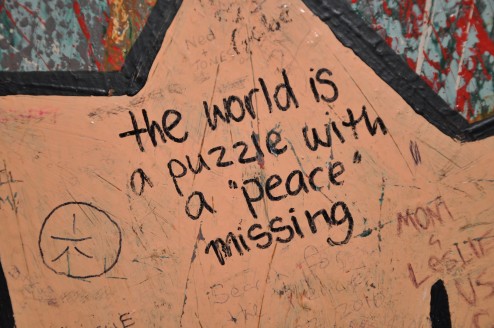

Sri Aurobindo writes of yoga’s synthesis between ‘on one side the Infinite, the Formless, the One, the Peace’ and ‘on the other it sees the finite, the world of forms, the jarring multiplicity, the strife…’ (414).[2]

This synthesis is you. Or as Alan Watts puts it “you are IT”.

When our mind, our body or our energy, is closed off—held tight like the bud of a flower—we cannot experience the beauty and creative expression that is every one of us.When we close our eyes we cannot see the beauty and creativity that surrounds us.

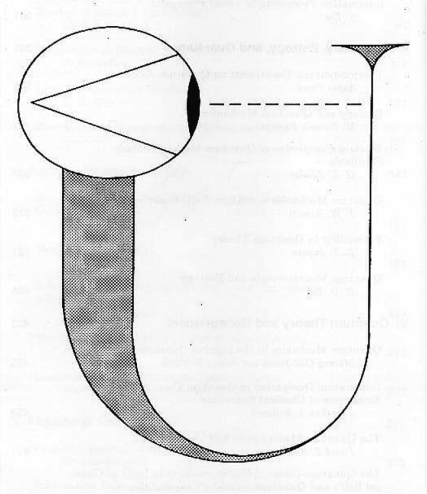

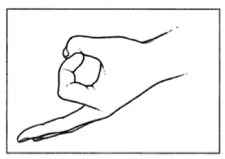

Let me illustrate yoga’s synthesis by describing the symbolism of a simple meditative pose. In this pose a person sits, lies or knees with their palms open, forefinger and thumb joined, and chanting “AOM”. The abhaya mudra (hand position) joining the forefinger and thumb symbolizes the connection between one’s transient self and one’s transcendent Self, the connecting of a part with its whole.[3]

The forefinger represents the ego or the temporal sense of the self as separate, and the thumb represents “God” (or “Brahman”, the one non-dual absolute reality or “Ātman”, the “true self” that is ultimately identical with the Brahman). This symbol allows one’s self to feel connected to one’s transcendent Self or “God”. The other three fingers that are stretched out represent the letting go of greed, ignorance and fear.

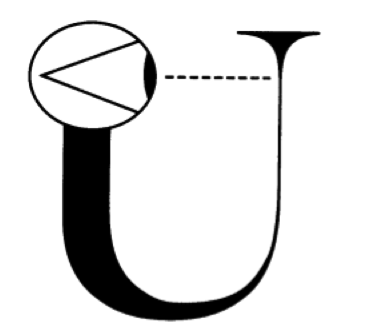

The chant and symbol “OM”, which is sung “Ah Oh Mm”, is considered to simulate the sound or vibration of our universe as it expands. One’s mouth moves from closed to open to sing “Ah”, representing the beginning of the universe. The tunnel shape of the mouth used to sing “Oh” simulates the expansion of the universe through time, and the closing of the mouth to sing “Mm” symbolises the end of our universe.

These rituals capture the central ideas of what might be thought of as process metaphysics, panentheism, integral thought, creativism , holistic worldview, or a “New Story” (even though it happens to be very very old): the joining of a part (you) with its whole (the Universe, or “God”).

[2] Aurobindi also includes with the latter the suffering and futility, which is reconciled in the bliss and calm of the One.