Critical Discourse Analysis is a study of LANGUAGE, IDEOLOGY, POWER and SOCIAL CHANGE. ‘Discourse analysis is not a “level” of analysis as, say, phonology or lexico-grammar, but an exploration of how “texts” at all levels work within sociocultural practices,’ says Candlin in the Preface to Fairclough. If you didn’t already gauge from the title then take this as your warning: this entry contains high levels of academic language. It is also disjointed and includes a lot of quotes (because I’m lazy).

Critical Discourse Analysis is a study of LANGUAGE, IDEOLOGY, POWER and SOCIAL CHANGE. ‘Discourse analysis is not a “level” of analysis as, say, phonology or lexico-grammar, but an exploration of how “texts” at all levels work within sociocultural practices,’ says Candlin in the Preface to Fairclough. If you didn’t already gauge from the title then take this as your warning: this entry contains high levels of academic language. It is also disjointed and includes a lot of quotes (because I’m lazy).

‘One crucial condition for social interaction in general and talk in particular is that people understand each other. This is possible only if we assume that social members have socially shared interpretation procedures for social actions, for example, categories, rules and strategies.’ (Dijk, 1985:2)

Critical Discourse Analysis is one of the “tools” I mentioned a few entries ago that can be useful for understanding the “taken for granted” systems of knowledge that we use in order to communicate. As such it helps us view the world in a more reflexive way – which not only makes people watching more interesting, it empowers us to interact with our reality in new and wonderful ways…

Critical Discourse Analysis involves looking at the “texts” that make up our realities, questioning their assumptions, identifying underlying ideologies, the connection between language and social-institutional practices, and how these connect to formation and maintenance of power structures (like The Pyramid).

These so-called “texts” range from books to movies, TV commercials, news stories, dinner conversations, education, parent-child relations, business meetings, and jokes. A “text” in this context is anything involving a communicative language – verbal and non-verbal.

Learning about this tool illuminates the ginormous impact that “texts” that surround us have on our lived experiences; how they operate as the key forces behind both maintaining status quo structures, and the initiation of social change.

Critical Discourse Analysis is intended to ‘critique some of the premises and the constructs underlying mainstream studies in sociolinguistics, conversational analysis and pragmatics, to demonstrate the need of these sub-disciplines to engage with social and political issues of power and hegemony in a dynamic and historically informed manner… to re-engage with central constructs of power and knowledge, and above all, ideology, to question what is this “real world” of social relations in institutional practices that is represented linguistically.’ (Fairclough, 1995:viii)

Critical Discourse Analysis might look at labels like “terrorist” and “counter-terrorist”, or “ally” and “enemy”… and examine not only the term, but how it is used by different people in different ways. The definition and use of terms such as these are clearly dependent upon which side you are on.

Take for example this funny clip:

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3ZNbfIPrrCQ[/youtube]

What might this tell us about the propaganda techniques of Neo-Conservatives? Or could this clip itself be propaganda against them?

So… what does Critical Discourse Analysis involve?

Dijk explains that ‘a typical ethnographical analysis of speech events features, for example, a description of the discourse genre, the overall delimination, social function, or label of the whole speech event, the topic (theme or reference), the setting (time and physical environment), the different categories for participants, the purpose of the interaction, the type of code (spoken, written, etc.), the lexicon and the semantics, the grammar (also at the discourse level), the sequences of acts (both verbal and nonverbal), and the underlying rules, norms or strategies for the actions or the whole event… And even this enumeration is not complete.’ (Dijk, 1985:9)

‘The method of discourse analysis includes linguistic description of the language text, interpretation of the relationship between the (productive and interpretative) discursive processes and the social processes.’ (Fairclough, 1995:97)

Fairclough refers to Mandel (1978) to describe the “postmodernist” features of “late capitalist” discourse that includes “post-traditional relationships” with relationships based upon authority in decline, both in the public and personal domain, for example, when it comes to kinship and self-identity ‘rather than being a feature of given positions and roles’ they are ‘reflexively build up through a process of negotiation’. Also the development of a “promotional” and “consumer” culture – with our strong emphasis on market and consumption rather than production. It is difficult not to be involved oneself in promoting because it’s part of so many people’s jobs and because it self-promotion is now part of our personal identity. (Fairclough, 1995:137-8).

Fairclough is calling for a critical social and historical turn. ‘It would seem vital that people should become more aware and more self-aware about language and discourse. Yet levels of awareness are very low. Few people have even an elementary metalanguage for talking about and thinking about such issues. A critical awareness of language and discursive practices is, I suggest, becoming a prerequiste for democratic citizenship, and an urgent priority for language education in than the majority of the population (certainly of Britain) are so far form having achieved it.’ (Fairclough, 1995:140).

Textual analysis involves two complementary types of analysis: linguistic and intertextual – that are a ‘necessary complement’ to each other.

‘Whereas linguistic analysis shows how texts selectively draw upon linguistic systems (again, in an extended sense), intertextual analysis shows how texts selectively draw upon orders of discourse – the particular configurations of conventionalised practices (genres, discourses, narratives, etc.) which are available to text producers and interpreters in particular circumstances…’ (Fairclough, 1995:188)

Texts are dependent on society and history in the form of the resources available but intertextual analysis is dynamic and dialectical in that the texts themselves can ‘transform these social and historical resources,’ “re-accentuate” genres and mix genres in texts. ‘Language is always simultaneously constitutive of (i) social identities, (ii) social relations and (iii) systems of knowledge and belief – though with different degrees of salience in different cases.’ (Fairclough, 1995:131)

Fairclough suggests developing “Critical Language Awareness” (CLA). It is important to try to increase the reflexive capacity of individuals.

Fairclough describes education as not only ‘a key domain of linguistically mediated power’ but is also a ‘site for reflection upon and analysis of the sociolinguistic order and the order of discourse’ by equipping learners with a critical language awareness as a ‘resource for intervention in and the reshaping of discursive practices and the power relations that ground them, both in other domains and within education itself.’ (1995:217)

With mass media generally acknowledged as the ‘single most important social institution in bringing off these processes in contemporary societies’ Fairclough recognises that ‘we also live in an age of great change and instability in which the forms of power and domination are being radically reshaped, in which changing cultural practices are a major constituent of social change which in many cases means to a significant degree changing discursive practices, changing practices of language use.’ (1995:219)

I think its encouraging to remember that society and culture are ALWAYS changing, language is ALWAYS evolving, and power structures are ALWAYS shifting. And I suppose we should be thankful that developed capitalist countries exercise their power typically through ‘consent rather than coercion’, ‘ideology rather than through physical force’ and through ‘the inculcation of self-disciplining principles rather than through the breaking of skulls’. If I’m going to be controlled, I definitely prefer it to be in this way.

References:

Norman Fairclough, Critical Discourse Analysis : The Critical Study of Language (London ; New York: Longman, 1995).

Dijk, Teun Adrianus van, Handbook of Discourse Analysis Book 3, (London ; Orlando: Academic Press, 1985).

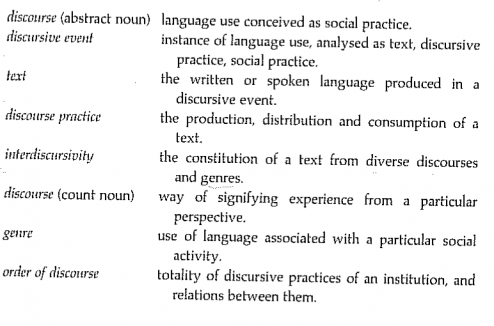

Picture:

Taken from Fairclough (1995) p. 135.

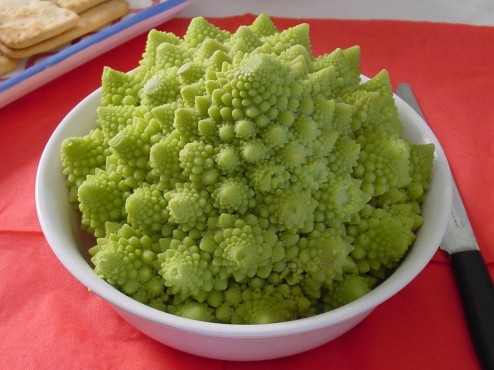

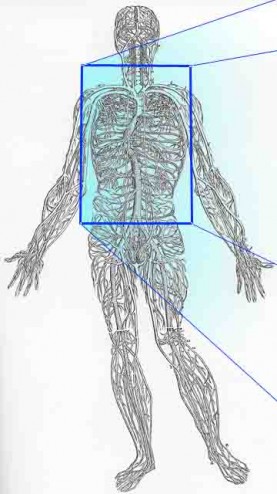

When I inside and outside my “self”, I see one thing: fractals. Fractals explain to me the microcosm and the macrocosm that our cells, bodies, societies, galaxies, and possibly universes and beyond, are a part of.

When I inside and outside my “self”, I see one thing: fractals. Fractals explain to me the microcosm and the macrocosm that our cells, bodies, societies, galaxies, and possibly universes and beyond, are a part of. A fractal is a shape that you can split into parts, zoom in, and discover the same or similar shape, times infinity. It’s almost magic, this pattern which extends outward and inward, seemingly to infinity. I’ll use the Koch Snowflake among others examples of fractals to introduce what I find a very exciting concept it to you.

A fractal is a shape that you can split into parts, zoom in, and discover the same or similar shape, times infinity. It’s almost magic, this pattern which extends outward and inward, seemingly to infinity. I’ll use the Koch Snowflake among others examples of fractals to introduce what I find a very exciting concept it to you.

Closer look at lightning

Closer look at lightning

[9]

[9] [10]

[10] Have you ever wondered why one Joker can beat four Kings. I mean, what does a joker have, besides a funny hat? How does a character based on the Fool, kick all these kings’ asses?

Have you ever wondered why one Joker can beat four Kings. I mean, what does a joker have, besides a funny hat? How does a character based on the Fool, kick all these kings’ asses? Christmas is full of stories and boxes, as are our lives. Every day, in every interaction, and in almost every thought, we seek to put the things we see, hear, smell, taste or feel in categorical boxes, and attach stories to them.

Christmas is full of stories and boxes, as are our lives. Every day, in every interaction, and in almost every thought, we seek to put the things we see, hear, smell, taste or feel in categorical boxes, and attach stories to them.