What is life really about? Walking on the beach this morning I had a sort-of epiphany, an experience of what I interpreted to be the two worlds created by the left and right brain. I realised there really are two distinctly different ways I can be in the world:

One way I could be in the world, as I walked along the beach, was to let my mind think about various things in my life: the targets to be met with my thesis, my plans to get to the end of the beach and tick off my day’s exercise checkbox. I walked enjoying the background beauty of the ocean, feeling happy about how good the fresh salty air is for my lungs, with a view to feeling healthy and being able to better achieve the next thing on my list.

Another way I could be in the world was to walk with a less-purposive, open focus on beauty of my surroundings. As I switched into this mode, I found myself pondering some deep questions: What does it really mean for human beings to be the “universe getting to know itself”? How does thinking of ourselves in this way change the way we, as a species, live? I felt a tear in my eye, I wasn’t sure why.

I looked at the apartments with views of the magnificent ocean, do the people that live there appreciate their privilege? Do they experience it in the kind of way that I had been walking, enjoying the beautiful background as they work to fulfil life’s requirements, ticking off checkboxes needed to maintain that life, to pay the mortgage, to feed their family, be successful at their jobs, and so on? How would a more balanced-brain affect that experience? I think it would be a subtle difference – it would be in moments like the one I was starting to have.

I began to really take in the beauty of the beach, smiling at the sea gulls pecking at bluebottles. I thought about the idea that I, myself, was expressed in the gulls, in the sand, in the stormy clouds that were appearing.

I decided to stop walking, and sit on the sandbank instead. I gazed out toward the horizon.

I closed my eyes and let an orange haze overcome by being. I felt the boundaries of my body’s skin fade into the background and a sense of unity come to the forefront. I am at once separate and connected—to everything around me, everything before me, and everything after me.

I felt myself observe and be in “the moment”—not as a singular thing—but as a flow, the continuous moment in the movement of time.

Time flows like the sea, a sustained present, inseparable from the past and future. Like the ocean’s mighty waves, time has no beginning and no end, it does not pause, it moves in and out, an expression of its own depths, of the atmosphere, and what lies beyond.

These two different ways that I could “be” as I walked along the beach correlated with the processes that Iain McGilchrist discusses in terms of our left and right brain hemispheres.

As I walked along the beach with my left hemisphere in charge, I was abstracted from the real world, using my time to tick boxes, calculate income, expenses, and the costs vs benefits of possible decisions, trade-offs between walking, eating brownies, working on my thesis, looking after my son, spending time with friends and family, renting vs trying to buy an apartment in one of the most expensive cities in the world. All these things that are important to our lives, but which are not actually real—they are not what life is actually about.

As I walked along the beach with my right hemisphere dominating, I had a sense of broad openness, allowing a spontaneity of thoughts and actions, letting the world’s true beauty touch my innermost essence of being. This is real, it is what life is all about.

I almost skipped the walk and went straight to the library, to make the most out of the few hours I had baby-free. If I had done so I’d have missed out on this experience of earth’s beauty, missed out on this epiphany, and I wouldn’t have known what I’d missed. I could have done the walk with a view to getting my day’s exercise, and again I wouldn’t have known what I’d missed in this experience and reflection upon what I see to be the real significance of life.

Letting myself walk without purpose had provided a space for development and understanding of myself, the world, and even my thesis and McGilchrist’s work, in a whole new and much deeper way.

The right hemisphere presents the world that is real and the left hemisphere represents abstracted parts of that world, the right hemisphere open and the left focuses on achievement within predefined bounds.

We need both hemispheres. We need our left hemisphere to help us organise, to give us things like the checkboxes that we use to hold ourselves accountable and achieve aims that we set out to achieve. Even more importantly, we need our right hemisphere to provide the context for these aims and actions, and to allow us to experience the joys that life offers us.

I suppose what I learned in this epiphany was how to switch into a more right brain mode of being, and the value of doing this.

If we spend our life letting our left brain tick boxes then we will keep ticking until the last checkbox “death” is ticked. Complete!

Instead if we switch into right brain mode we can cultivate the art of living, sensing, experiencing, being conscious, reflexive, truly appreciating the beauty, valuing the connections, and being the flow of the continuous present.

Perhaps in a balanced brain mode, the work of our left brain can be in the service of the right brain, the abstract working for the real, parts working for the whole, instead of the other way around. For that is what life is really about.

Recent work in neuroscience, for example on stroke survivors and using new technologies that light up when different parts of the brain are being used, are illuminating this in exciting ways.

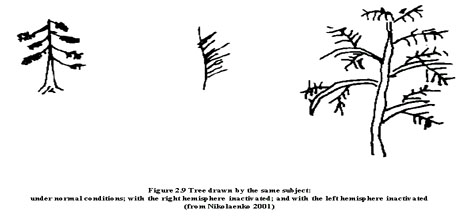

Recent work in neuroscience, for example on stroke survivors and using new technologies that light up when different parts of the brain are being used, are illuminating this in exciting ways. First it is important to make clear, as McGilchrist does again and again that the idea that the left hemisphere gives us reason and language, while the right hemisphere gives us images and emotion is false: we need both hemispheres in order to deal with these things, from reason and emotions to interpreting language and images. McGilchrist writes: ‘every identifiable human activity is actually served at some level by both hemispheres’ (1).

First it is important to make clear, as McGilchrist does again and again that the idea that the left hemisphere gives us reason and language, while the right hemisphere gives us images and emotion is false: we need both hemispheres in order to deal with these things, from reason and emotions to interpreting language and images. McGilchrist writes: ‘every identifiable human activity is actually served at some level by both hemispheres’ (1). In this RSA 21st Century Enlightenment animation to McG’s TED Talk you can get a good introduction to these ideas:

In this RSA 21st Century Enlightenment animation to McG’s TED Talk you can get a good introduction to these ideas: