Love is blind. It makes you do crazy things. Spontaneous things. Fun things. And sometimes really stupid things. I think when it hits you you know the pain that lies ahead, yet you jump in anyway. The first time I laid eyes on her I knew. Maybe it was her bright orange skin, maybe it was the way she popped her top on cue, or maybe it was her cute button nose. It was love at first sight. Like the trajectory of most love stories I figured this relationship would come to an end. But what I didn’t know was how fast it would happen.

This is a story of false hope and empty promises. This is a story about living with intensity and adventure. This is a story of loving fully and learning to let go if one’s life’s optimal trajectory calls for it. This is the story of the very short life and times of me and Kombi Xee.

I had been looking for a kombi for a couple of months, but none were like her. Mirroring my taste in men the kombi’s I was interested in lived too far away or were already taken, until I met Xee. She was perfect. She needed a little work on the body, but nothing that couldn’t be fixed. Most importantly, so the seller assured me, she was mechanically healthy with an recently reconditioned motor, no oil leaks, good brakes and new tyres. She would easily pass rego in March. The pressure of competition bid me to jump in. “I’ll take her.” I said, offering the asked price.

Like the beginning of most relationships, the honeymoon period was wonderful. As I learned how she worked, exactly where to let the clutch out and work her gears, things only got better. I projected images of our glorious future together: long coastal drives, sleeping anywhere, early morning swims, weekend getaways, lots of time to read and write and reflect and keep inspired.

Our first trip to Jervis Bay was everything I dreamed. She made driving fun. I sailed by day, and slept by the waters-edge at night.

Ahimsa Sailing Klub Inc

Ahimsa Sailing Klub Inc

It was only two nights, but it could have been weeks.

Xee slowed life down a notch. Time didn’t matter with her. I couldn’t go anywhere fast so I no longer tried. Chugging along we strived out way up hills, and sped at full speed back down the other side. The hippy inside me lit up as I embraced the things the 70s stood for like peace and freedom and all those ideals I think too much. Now I wasn’t thinking about them – I was feeling them. I was them.

Kangeroos in our backyard!

An afternoon at Murrays Beach

After one night back at home we left for our second trip: the Northern Beaches.

After a day’s work in Belrose I parked Xee in Mona Vale, up on the headland with a magic view of the golf course, beach, ocean, horizon and beyond. I went for a twilight swim, had a cold shower, read a bedtime story, and fell into a blissful sleep. At sunrise I repeated the above, and drove back to work. Work would now become a weekly holiday, or so I thought…

Men, women, kombis… who knows what causes them to crack. But when a relationship goes to hell, there’s no knowing what’s going to happen next. I’d been with Xee for less than a week when the romantic bliss came to an earth-shattering end.

In the space of one hour, my side mirror fell off doors, the drivers windows refused to close, at red lights on hills she stalled, spat, spluttered, and died. I powered her back up. Without a mirror I was scared to change lanes, I missed turn offs, and every slight hill she got worse.

People around us stopped and stared.

“Come-on baby, don’t give up on us yet!” I pleaded. But this wasn’t your ordinary domestic fit.

Xee delivered me home and took her last breath.

That night and the following two weeks were filled with doctor visits and hospital stays – from NRMA dudes telling me she was only running on two cylinders through to tow truck drivers and finally a kombi-specialist who delivered the final blast of bad news: it was fatal.

“Try to fix the cylinders and you’ll open a Pandora’s Box of problems.” Steve the mechanic shook his head. “She needs a new motor. I’m sorry to say but you bought a lemon.”

As if stealing my heart and my dreams wasn’t enough.

So here I am. In love with a kombi that just doesn’t want to love me in return.

“The timing just isn’t right for us,” she whispers to me, shedding a tear.

I could spend another $5k on her to get her back on the road, but that’s scraping the bottom of the barrel, using up money I need for trips to conferences and universities in Europe and the US later this year. Part of me wants to stay in Australia, but I know that’s not my path. And so, sad as it is to say, I know it’s time to part ways.

Some relationships last a long time, and some only a short time, but all relationships must eventually come to an end. The trick is to know when to say yes and give it your all, and when understand it’s best for both parties to let go.

Xee needs someone who can invest the time and money that will get her back to health. She needs to be in a relationship with someone who can give her the love she deserves.

without

Is there something that can be learned from this story, about loving without attachment?

Might this apply to love for a friend, boy/girlfriend, and even for material things like houses and kombis?

Is it possible to love without selfish motive? To love another in a way that puts whatever is best for the other before one’s own desire to be with them?

As I look back over our beautiful week together I know I will always remember the life and times I shared with Kombi Xee.

These moments of the past that will remain present, just a thought away, for the rest of my life.

The best human relationships are like that too. Relationships where moments of the past were lived so fully present that simply the thought of it brings the moments back to life. No matter how long or short a relationship, the best one’s live on forever: continuing to inspire, energise and make you smile.

The last month – the one week of highs and three weeks of lows that followed – are a reminder of life’s roller coaster. It might be exciting at times, scary at other times, and a little dull as you wait in line to do it again. But you can’t have one without the other. The lows are what makes the highs so great. The closeness of death makes life so exhilarating.

Kombi Xee has reminded me of the important things in my life: she reminded me to slow down, to allow time to reflect, to value experiences over money and things (even kombis), to be able to shrug my shoulders when frustrations occur, to have faith in the universe, and that if you follow it’s “signs” guiding you intuitively toward your “optimal trajectory”, the universe will take care of the rest.

Xee reminded me of the importance of letting go: letting go of fear, letting go of the things I tell myself I “need”, and to remember that you never know what new adventure lies beyond the horizon.

Me in Kombi Xee

Me in Kombi Xee

Photos: most taken by my talented friend Melissa McCullough, and a couple from Sveinug Kiplesund (who’s a pretty good photographer too 😉 ).

HAVE YOU FALLEN IN LOVE WITH XEE???

I am going to put Xee on ebay, so if you feel you’re up for the challenge of this exciting but exhausting lover, then check it out:

http://cgi.ebay.com.au/ws/eBayISAPI.dll?ViewItem&item=260742402596#ht_614wt_905

More details about her:

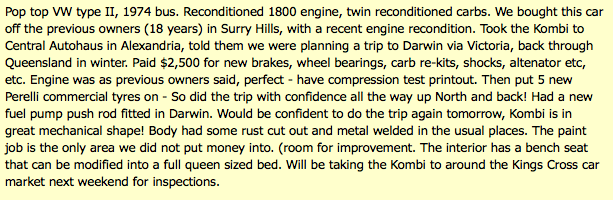

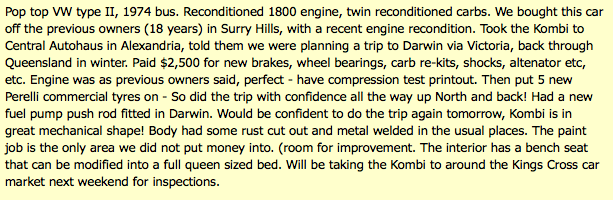

This is the original ad I responded to off Gumtree:

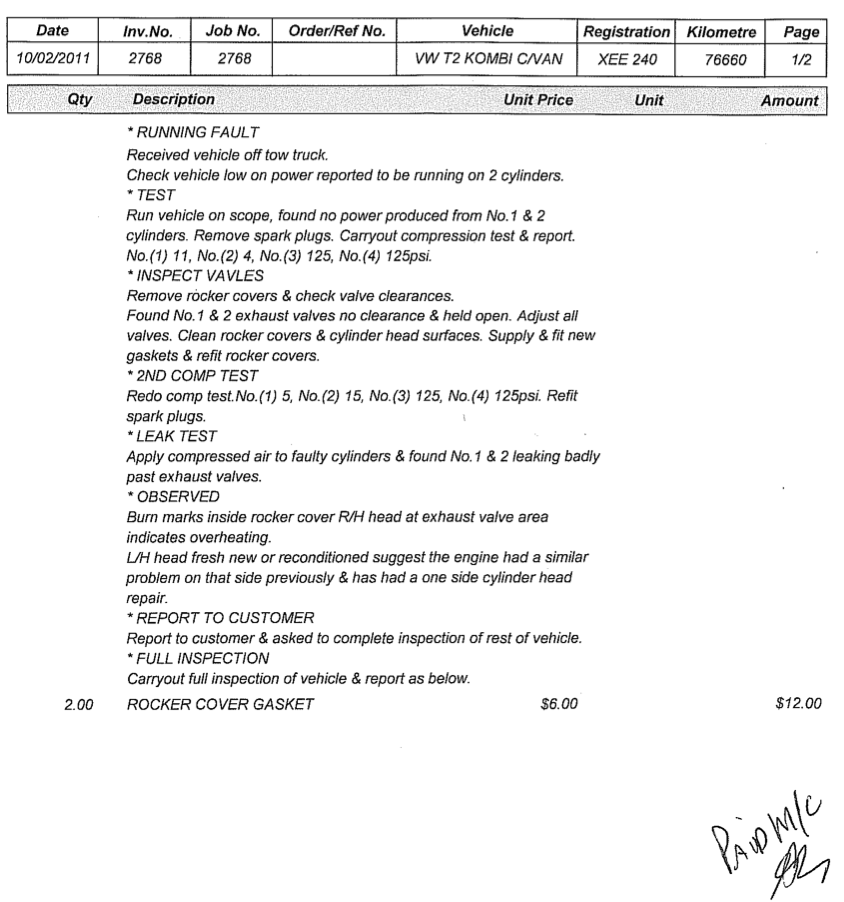

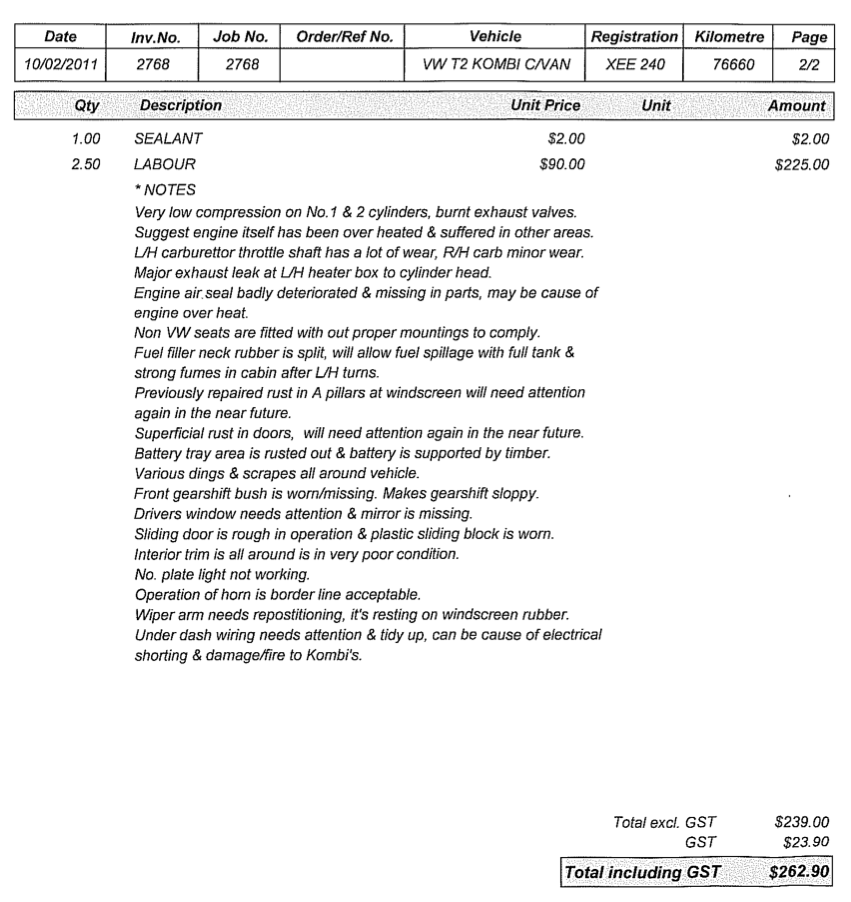

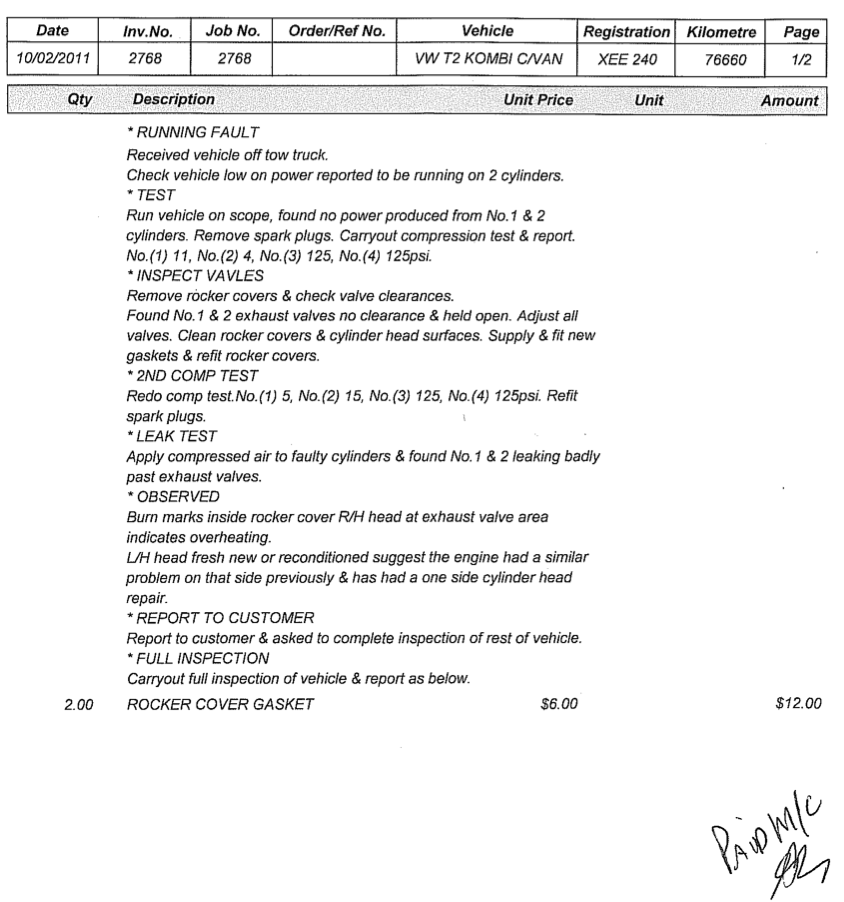

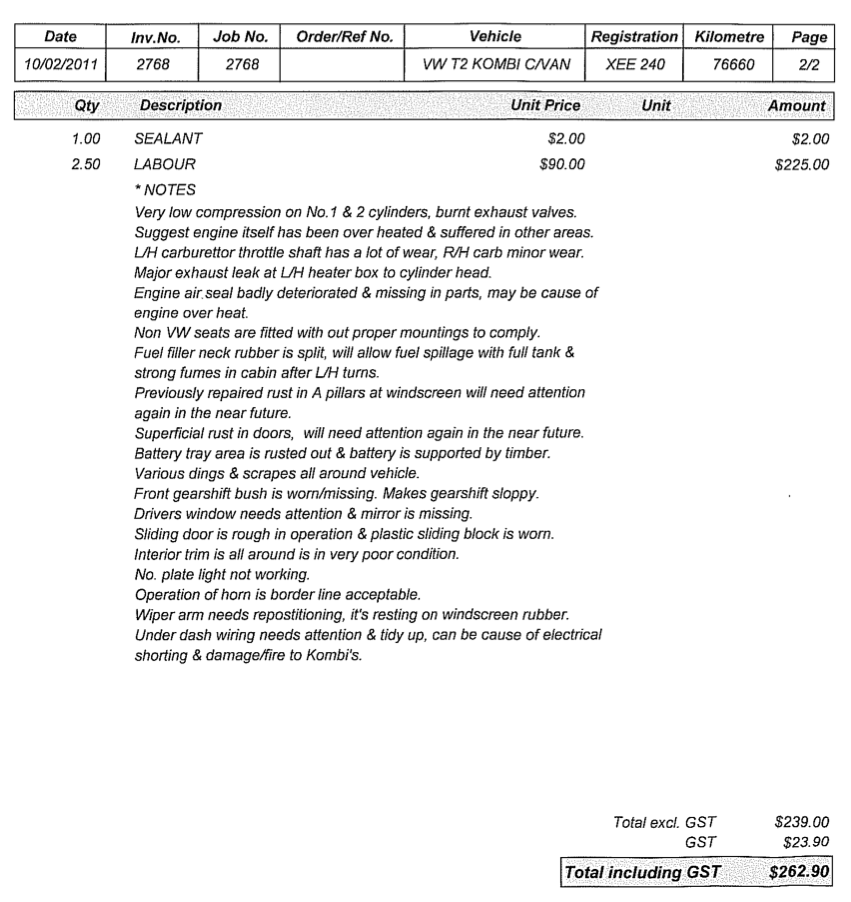

And this is the mechanic report I got last week:

Even in Europe I seem to be drawn to South American cultures. Some hippies from Bolivia and Venezuela, as well as the Canary Islands, were selling jewelry on the street. Before long we were playing music, drinking beer, and joining the hippies and a crazy American family on an adventure to the anarchist town of Christiania.

Even in Europe I seem to be drawn to South American cultures. Some hippies from Bolivia and Venezuela, as well as the Canary Islands, were selling jewelry on the street. Before long we were playing music, drinking beer, and joining the hippies and a crazy American family on an adventure to the anarchist town of Christiania.

I hate the word “evil” for two reasons: (1) because of its religious connotations and (2) because its definition is relative and constantly changing. Same goes with “sin”. Two words with definitions that change depending who is in power.

I hate the word “evil” for two reasons: (1) because of its religious connotations and (2) because its definition is relative and constantly changing. Same goes with “sin”. Two words with definitions that change depending who is in power.

Imagine a world where being 180cm, 60kg, with long blonde hair, makes you AVERAGE. In Scandinavia, for the first time in my life, I felt short. It was a strange feeling. Used to towering over people and always kind-of standing out because of my height, blending into the crowd provoked a new stream of thought.

Imagine a world where being 180cm, 60kg, with long blonde hair, makes you AVERAGE. In Scandinavia, for the first time in my life, I felt short. It was a strange feeling. Used to towering over people and always kind-of standing out because of my height, blending into the crowd provoked a new stream of thought.

Soon I am off to Europe followed by the United States, with a very big question mark surrounding my return date. I’m booked to leave 9 weeks from yesterday and be home just in time for Christmas… but I really have no idea what my future holds. Exciting as this sounds, when it comes the details, life in the 21st century can make preparations and decisions surrounding uncertainties a massive anxiety-filled pain in the butt.

Soon I am off to Europe followed by the United States, with a very big question mark surrounding my return date. I’m booked to leave 9 weeks from yesterday and be home just in time for Christmas… but I really have no idea what my future holds. Exciting as this sounds, when it comes the details, life in the 21st century can make preparations and decisions surrounding uncertainties a massive anxiety-filled pain in the butt. Ahimsa Sailing Klub Inc

Ahimsa Sailing Klub Inc

Me in Kombi Xee

Me in Kombi Xee

Content in living out your life: work, money, weekends, holidays, home, kids… and then something happens: a cataclysmic event changes everything.

Content in living out your life: work, money, weekends, holidays, home, kids… and then something happens: a cataclysmic event changes everything.