After two years of anticipation, in June this year I attended a conference called “Seizing an Alternative: Toward an Ecological Civilization”, which brought together many of my favourite scholars. I was like a teenager anticipating a music festival with all their favourite bands. Such a geek!

Around 2000 people attended the conference from around the world, splitting into 12 sections and 82 groups to workshop different ideas, uncover deeper understandings of the causes of the ecological crisis, and apply their findings to evolve worldviews and world-systems toward ecological civilization.

The conference began from a common point of recognition: that humanity is deeply alienated from nature, and that this alienation underpins humanity’s impact on Earth’s ecosystems. This has brought about a global ecological crisis with symptoms including climate change, vast and fast extinction of species, loss of top soil, and so on. There seemed to be a common acceptance that a large part of the problem is greed, interest groups and multi-national corporations. At root of these factors are assumptions about the world that have caused a sense of alienation from it.

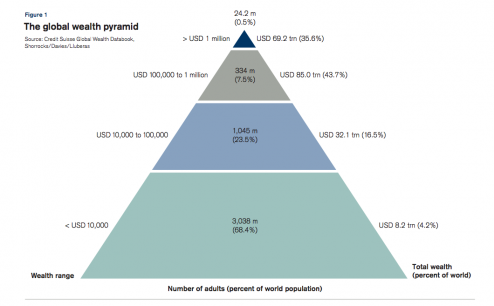

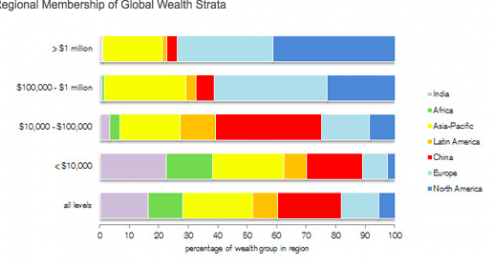

How did the alienation arise? How is it linked to our beliefs about ourselves and about the world? How can the power shift from the hands of the 1% to the majority, and how can people and the planet be prioritised over monetary profit?

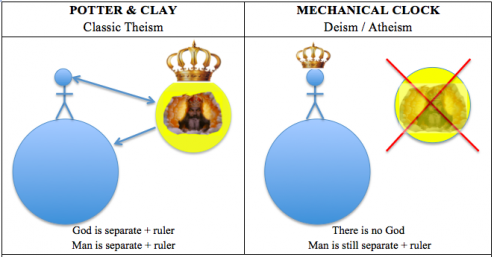

The conference critiqued the deep underlying assumptions at root of most western understandings of the world (categorised as “substance metaphysics“), and envisioned what an alternative world-system would look like based on alternative assumptions (categorised as “process metaphysics“). This sounds abstract. More simply put, it is a shift from seeing the world as made of independent things that operate like balls on a billiard table; to seeing the world as a web of interdependent processes.

For example, rather than seeing yourself as an individual who is separate from your parents, your upbringing, your education, the social structures and economic factors that influenced who you are today; you come to see your self-in-context and as an ongoing process—understanding that these relationships and influences have shaped certain aspects of your life and within these structure you have had choice (and still have choice) to shape other aspects of your life (including, in time, changing these structures).

In the conference program, John Cobb Jr provided an introduction to set the scene for the discussions. This is a bit of a summary of what the conference was about, based on my notes from the talks I attended (largely using the speakers’ words) and Cobb’s introductions (references are the pages in the program).

The metaphor and community of Pando Populus

The conference symbol “Pando” stands as a metaphor for understanding its key message.“Pando” is the ‘largest and oldest organism on Earth, a quaking aspen that extends over 100 acres in southern Utar’ . It is estimated to be between 12,000 and 80,000 years old. It looks like thousands of individual trees, yet these share a single root system—‘It is one tree’! (8)

![By J Zapell [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://julietbennett.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/1024px-FallPando02-494x327.jpg)

This is not many trees, it is connected with one root system—it is Earth’s oldest single organism!

Pando Populus has been set up as a forum, which includes YouTube videos of keynotes, summaries of the sessions below, and other resources for being part of this community. It goes beyond finding ‘isolated fixes’ instead aiming to ‘challenge basic assumptions of the modern industrial world and propose ecological alternatives. It asks questions like:

- ‘What would business and finance look like if the aim of creating a thriving ecosphere becomes the goal of the economy?

- What would religion be like if it were to focus on world loyalty as opposed to sectarian or national loyalty or world escape?

- How would the university be reshaped if it accepted responsibility for the future of the Earth rather than attempt to be value-free?’

These are the types of questions that were addressed at the conference. It is an ongoing discussion, there are no fixed answers but the process of seeking them, of envisioning a new way of being in the world, is the answer. And here is a snapshot of this contribution to that process:

Selection of notes on Keynotes:

Bill McKibben wrote the first book on climate change 26 years ago, and is now the leader of the 350.org movement who are campaign for divestment of fossil fuels and investment in green energy, in order to reduce the carbon in our atmosphere back to 350 parts per million (ppm). We are now at 400 ppm and adding about 2 ppm into the atmosphere per year. What can you do? Campaign for divestment: call government representatives, corporations, universities, etc. ask them to divest from fossil fuels. The fossil fuel industry needs to be replaced with a green energy industry.

John Cobb Jr is a (if not the) leading process thinker alive today. Cobb criticised “TINA” thinking that “There Is No Alternative”. One can campaign for an isolated issue, but in the end it might not make so much difference e.g. saving the whales (now threatened by their food supply due to acidification and overfishing), the black civil rights movement (now look at it), feminist success (now women are hired as workers like everyone else), voting (now congress need to please financial supporters). He posited that we need fundamental change, we need to address issues by addressing the roots of the issues.

Cobb said that as long as we see the world as a machine, attempting to see it “objectively”, we are not going to treat it as being valuable. We need to overcome the 17th century thinking that nature is a machine, and the misplaced extension via Darwinian thought that thinks humans are machines as well. Instead we need to see, as Henri Bergson, William James and Alfred North Whitehead did, that humans are a part of nature, and both humanity and nature are fully-alive.

Whitehead’s philosophy of organism is the most comprehensive replacement of mechanistic thinking, providing a process-based metaphysical system on which this ecological thinking is based. ‘We do not need to recreate the wheel – it is there, but we still need to question and build and solve issues arising using this alternative mode of thought.’

Mary Tucker Evans was taught by Thomas Berry and runs The Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology. Evan’s promotes ecological civilization through a new worldview and new ethics, via religious traditions entering an ecological phase. One way of encouraging this shift is through what Berry called “the New Story” – a macro telling of history that can be found in Journey of the Universe and Journey of the Universe Conversations with Brian Swimme. This story is also being told in Big History, that David Christian developed a curriculum for and thanks to Bill Gates’ support is spreading through schools and universities across the world. Evans was involved in drafting The Earth Charter, which promotes ‘ecology, justice and peace’.

Dr Sheri Liao is a leading environmental activist in China, who discussed the Global Village of Beijing project, and some of the ways in which process thought is having a positive impact in encouraging ecological development in China.

Herman Daly is an ecological economist who points out that the problem is our commitment to growth. His thought is associated with the steady-state economy of John Stuart Mill, promoting a stabilization of population and slow down the economic metabolism so to prevent resource depletion. Instead of development through quantitative growth, we should develop through qualitative growth. We feel as if we are isolated individuals yet we are people-in-community. Daly suggested the “Genuine Progress Indicator” replacing the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), in order to prevent horrible costs such as oil spills being registered as having a positive economic impact.

Daly also linked getting off the growth path to helping avoid war, which is so often due to unequal economic growth and fighting over resources. We need a paradigm shift away from self interest. If we really are self-interested we should try to be better off rather than having more. The economy and even money has been created from the human imagination, and we can evolve it in new directions if we can imagine it!

Vandana Shiva spoke with compassion for all of Earth’s community, not just the ‘mafia economy of the 1%’. Shiva is a quantum physicist and ecofeminist who promotes a new worldview and sustainable agriculture. She discussed biopiracy, the use of pesticides and chemicals on food, the way that corporations are stealing democracy from us, the tendency for extraction and exploitation, ways that the Green Revolution violated every law of nature, that 80 men control 50% of the world’s wealth, and the need to place emphasis on process + relationships. I had lunch with this 2010 Sydney Peace Prize recipient earlier in the year, so in the interests of space I’ll let that post tell more than I can here.

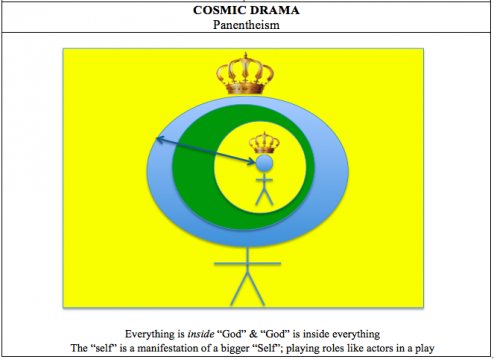

Phillip Clayton, whose books on panentheism and “organic marxism” have had a great influence on me, emphasised the need to ‘free ourselves form the modern dichotomy of objectivity and subjectivity’, and for science to apply a ‘plurality of methods’. We need to move to a paradigm that sees that ‘nature is alive‘, recognising that we are a ‘community of agents’, and are obliged to see others’ as agents as well.

David Ray Griffin is a leading thinker in process thought and panentheism, and is the leader in bringing process thought (or ‘constructive postmodernism’) to China. His influence is global and inspirational. Griffin’s keynote address was the closing of the conference. He explained the ways that Whitehead solves a number of contradictions, between different religions, and between religion and science. Griffin posited time as nonemergent, as something that ‘goes all the way down’. We live within a succession of universes inherited from previous universes. Emphasised the need to show scientists and philosophers that theism can exist without supernaturalism.

Griffin also pointed out that there are now universities in Europe where students can study and specialise in Whitehead. I reckon it’s about time we get one in Australia as well… As Cobb summed, ‘we need to point out that people have a metaphysic and what a stupid metaphysic they have. It’s time for a new one.’

Section 1 – The Threatening Catastrophe: Responding Now

‘We face the possibility of an irreversible end of civilization and even of the human species. Today the most urgent threat is climate change. … Avoiding nuclear war and developing alternatives to war in general have immediate urgency. … Increased population and decreasing resources point toward disastrous shortages.’ Combined with ‘many of the efforts to increase production speed climate change.’ The shortage of resources is also a ‘factor in current wars’. Furthermore, ‘financial disasters’ are a constant threat as ‘we have developed an economy so dependent on global financial institutions,’ which means ‘the whole system of producing and exchanging goods is threatened. … Democracies are becoming “corpocracies.” Financial institutions manipulate both government and public opinion.’(12)

‘The likelihood, nature, and scale of the disasters brought about by modern civilization make it imperative that in envisioning the future we consider the fundamental assumptions that have driven the modern world to self-destruction. We have no alternative but to think civilization anew, this time in an ecological framework. “Seizing an Alternative” as a while focuses on laying the groundwork for building a different civilization on different fundamental assumptions.’ (12)

Section 2 – An Alternative Vision: Whitehead’s Philosophy

‘Each of us acts against a backdrop of basic assumptions about the world that have us living out the results of philosophy whether or not we think about them, or participate in criticizing or shaping them. … the value of philosophy is the kind of broad, “critique of abstractions” that Alfred North Whitehead named, and the wisdom-seeking we all have to engage.’ (16) We need to ask: what is “common sense”, what is our purpose and what are aiming for?

‘Whitehead is the focus of the “Seizing an Alternative” conference because few recent philosophers were as interested as he in this broad understanding of philosophy – that is, big ideas that really make a difference in the world. Further, no other philosopher in the past century has so rigorously and systematically challenged assumptions of the modern world and proposed fundamentally ecological alternatives. … Whitehead called his magnum opus, Process and Reality, an essay in cosmology. Cosmology, in his understanding, offers a comprehensive view of the totality of things, including both the world studied by the natural sciences and the world of human experience and activity. … Whitehead’s cosmology opens the door to discuss many topics that are neglected in most contemporary thought. … Whitehead’s cosmology offers hope that matters of spirit can be integrated in an attractive way with science in a single coherent vision. This rethinking of ethics and religion is essential if we are to create a fully integrated and well-rounded ecological civilization.’ (16)

‘A fundamental feature of the dominant forms of modern philosophy is treating each entity as if its essential being is self-contained. The only relations affirmed are “external relations,” that is, relations that do not fundamentally affect the entities that are related. … Ecological thinking, on the other hand, views the relations among things as essential to their being. These are “internal relations.” Whitehead calls them ‘prehesions,” and he shows how they fundamentally constitute all actual entities. [Whitehead] is in the fullest sense “the philosopher of ecological civilization.” Helping other philosophers to understand his unique contribution is an important step in breaking the habits of thought that have led modernity to self-destruction.’ (17)

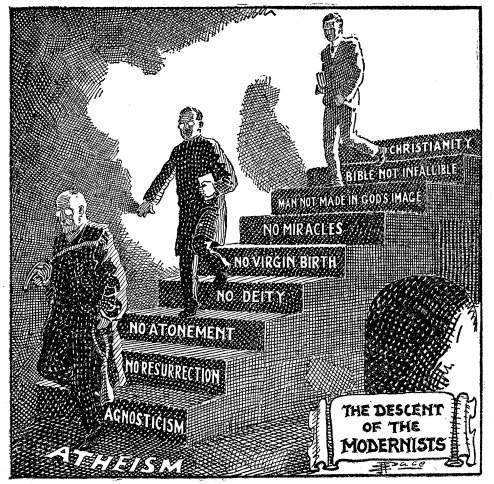

Section 3 – Alienation from Nature: How it Arose

Why do human beings think that we are separate from and more important than nature? This ‘sense of separateness … seems to have developed with agriculture and the building of cities. … Civilization led to almost complete alienation decisively through the European Enlightenment of the seventeen century and its produces: modern technology and the industrial revolution. … Rene Descartes, who developed the Enlightenment vision most profoundly and influentially, is known especially for his radical dualism of the human soul, on one side, and mere matter in motion on the other.’ Positive effects of this include the ‘critical thought’ that led to ideas about the ‘dignity’ of ‘human beings’ which ‘supported the ideas of human rights and even of a fundamental equality of all human beings.’ In the 19th century: ‘Darwin showed that human beings are a product of biological evolution, so that they are fully part of nature. This opened the door to re-thinking nature as having some of the properties Descartes attributed only to the human soul.’ A Whitehead’s philosophy is a response to ‘the new understanding of how human beings came into being.’ Cobb warns that ‘we are working against the now dominant vision of our universities and our culture general. The commitment of the sciences to methods associated with nature’s purely objective existence (without a subjectivity of its own) was very strong.’ Humans are studied as objects, ‘as very complex machines’. ‘Where Descartes had objectified nature, post-Darwin human beings became objectified too.’ According to Cobbs, while the scientific method can be fruitful, it need not shape our view of reality. (20)

‘Enlightenment dualism was replaced in late modernity by reductionist monism. The Enlightenment led people to understand themselves as responsible citizens. The new reductionistic monism supported the industrial system that represents us as cogs in the wheel of the economic system. … It’s the difference, as Alfred North Whitehead put it, between “nature lifeless” and “nature alive.” If we deeply understand nature as a whole to be alive as much as we experience ourselves as alive, we will richly experience our kinship with other living things, especially other animals. Perhaps, then, we can begin the healing process.’ (21)

Section 4 – Re-envisioning Nature; Re-envisioning Science

The ‘Cartisian view of nature was materialistic and reductionistic’, it has fostered a ‘deep alienation’ from the ‘natural world’. ‘Descartes’ dualistic metaphysics by no means initiated this sense of human beings as distinct from nature and above it, but his formulations have played a particularly important role in the world of science and technology. They have shaped our educational institutions and most of our academic disciplines into disjointed categories and disciplines. They have sometimes further contributed to alienation by asking us to reject common sense in our view of what is real.’

However, ‘recent discoveries of science have led to new and more adequate views of nature … quantum theory, evolutionary biology, ecology and neuroscience.’ Cobb points out that ‘the new understanding of the natural world still struggles to displace the Cartesian one that has dominated scientific thought for centuries. … The scientific establishment tends to treat the new discoveries as ‘anomalies,” and largely ignores their implications for basic assumptions.’ Slow changes are taking place in the academy, while outside and with some help from within, ‘a whole new vision of the natural world is emerging that opens up ways of thinking about the world as being more than simply collections of moving matter.’ Based on evolutionary understandings, but not mechanistically reducing nature to ‘matter in motion’ à also shows ‘that novel realities are coming into being again and again. … The sciences that are adequate to understanding the emergence of life and directed action in the world are important, therefore, for more than just getting our facts straight; they help us to know what it means to inhabit this planet. They prompt us to tell the scientific story in ways that are intrinsic to the natural world and our deepest experiences within it, while still allowing for the rigorous scientific study of nature. They represent a shift in understanding important for creating scientific conditions necessary for a thriving ecosystem.’ (24)

Section 5 – Ecological Civilization

‘Without a vision of where we need to go, our efforts are not likely to have the needed motivation or coherence.’

The alienation is not intrinsic to humanity, it is cultural, it is reflective of ‘erroneous thinking about the natural environment’. Is an ecological civilization possible? If so, what would it be like?

‘Any image of a sustainable world must consider its carrying capacity’ including consumption, number of people, other species, etc. ‘A truly ecological civilization is one in which human beings understand themselves as one species among others. It is concerned both with every individual creature with which we share the planet, and with the ecosystem as a whole. It will give a great deal of attention to what we eat and how we produce it. And at every step it will consider how that which contributes to sustainability can also contribute to personal enjoyment and social well being.’ (28)

Section 6 – Reimagining and Reinventing the Wisdom Traditions (A)

Axial Ways – term coming from Karl Jaspers “Axis” of human history – Greek philosophy, Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Confucianism and Taoism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, Zorastrianism. ‘The world religions are often viewed as having failed in their relations to culture, to one another, to science, and to the natural world. Although there is much justification for this criticism, the actual situation is far more complex, and in all these respects there have been dramatic changes for the better. Especially because the secular world offers no better option, we urgently need the further development and transformation of the great wisdom traditions if we are to build an ecological civilization. They should be re-imagined and re-invented – not discarded.’ Cobb emphasizes the “world loyalty” (using Whitehead’s term) found within the traditions, rather than ‘sectarianism, nationalism, or escapism.’ (32)

Section 7 – Reimagining and Reinventing the Wisdom Traditions (B)

The Hebrew prophets tended to focus on outer life and justice, while in Asia a key focus was ‘the systematic and articulate description of the inner life, together with the idea that we can choose to shape it.’ Cobb points out that ‘internal life’ affects ‘outer life’. … ‘what today most people mean by “spirituality” is the ordering and enriching of the interior life to which India and China contributed so much.’ Cobb warns that too much focus on inner life can lead to a lack of focus on outer life. ‘We need their re-development in the context of our new awareness of what we are doing to our environment.” While Greek philosophy is not usually thought of as spiritual, Cobb points out that ‘many of the Greek philosophers were quite concerned to guide the shaping of the inner life.’ He links this to Neo-Platonism which he believes ‘can readily be understood as a spiritual movement’ He also links this to ‘Indigenous people who have eschewed “civilization” and maintain traditions continuous with practices and attitudes developed long before the rise of civilization.’ (38)

Section 8 – Reimagining and Reinventing Education

“Our existence is more than a succession of bare facts” Whitehead

Education is not only done at schools, it is also conducted in homes. Historically the latter has been dominant, yet today in the ‘modern secular world’ most education is ‘controlled by the state’ … ‘There has been too little reflection on this situation. Historically, education has been at least as much about values as about facts and skills. To live without conscious values is to fall short of being human. Schooling inevitably communicates values, and by failing to encourage reflection about them, it fails to make them conscious or effective. This reflects the situation of the modern secular state, which is in general unclear about its values.’ Taking the US as an example Cobb explains how since WW2 the ‘values of modern Protestant Christianity’ have influenced American people including their encouragement ‘to accept authority without much questioning a’ and considering “values” and “religious beliefs” to be ‘a private matter’ not for the classroom. ‘Higher education celebrates itself as “value-free.” … The topic on which research is done and the use of its product are matters of indifference. The university serves whoever will pay for the research. The students are attracted to the university on the grounds that they will earn more by completing a university program. In short, the default value, when the values of the Axial traditions are set aside, is money. This is not the outcome that those who opposed Protestant hegemony had in mind. It is diametrically opposed to ecological civilization. For those who want to steer our nation and others away from the precipice toward which the world is heading, reconsideration of our schooling system much be a very high priority. What would happen if we collectively decided that instead of freeing education from all values except money, we directed education toward building an ecological civilization?’ (42)

Section 9 – Reimagining and Reinventing Bodily-Spiritual Health

Cobb states that ‘ecological civilization would end the reign of Descartes and put body, mind and spirit back together again’ bringing about a ‘wholeness of body, mind, and spirit’. ‘Westerners have learned from India and China that breathing and bodily movements contribute to spiritual realization. From many sources we know that psycho-spiritual problems express themselves also physically.’ There is a growing ‘awareness of dimensions of reality not accessed by the sense organs’. Cobb states that ‘’I judge that the most promising single movement today working for ecological civilization is eco-feminism.’ (46)

Section 10 – Reimagining and Reinventing Societies and Social Thought

‘A basic assumption of modern thought is that everything can be reduced to its parts, the whole being nothing more than their sum.’ This view has ‘no primary place for ecological relations.’ Cobb emphasises that in the dominant view ‘Relationships are always derivative of individual units, and lack status as being fundamentally important to the nature of things.’ We need personal development (as in positive psychology and nurturing of values), community development, social and political development, education and cultural development, and the development of healthy environment/ecosystems. It is common to emphasise the personal and community without looking at the implications for the world at large including social, political and ecological implications of personal action.

‘Although the quality of personal life is important, and much can be gained by focusing attention on it, all such achievements depend on social and ecological conditions.’ It is important to consider ‘many features of social order […] quite separately from the issues of full realizaiton of the potential of individuals.’ Cobb points to the ‘reciprocal relation’ between individuals and society, with the society impacting on the virtues of individuals and these virtues of individuals impacting back on society. In academic jargon this is to say that it is not structure OR agency, but agents-within-structures. ‘An ecological civilization would define human society as persons in community. This discourages both the view that society is simply a collection of individuals and the reduction of the importance of individuals in favour of the society as a whole. Individuals become full persons only in the context of community, and societies become authentic communities only as the people who make them up become strong persons.’ This can impact conversations and developments in academic, corporations and beyond. (50)

Section 11 – Reimagining and Reinventing Culture

‘Every human society has its own culture. This is true of families … distinctive cultures in each school and church and civic organization. If one joins a new society, one sense what is expected and adopts it, or one never really belongs.’ Cobb considers “meaning” to be constructed through “references”. ‘Languages organize life and environment in different ways, so that the translation among them is never perfect. … meanings go far beyond that. They refer to emotions, moods, purposes, memories, hopes, and fears. They refer to aspirations and dreads, the sacred and the demonic, the requisite and the forbidden. They shape both thought and action and, more deeply, feeling and purpose. … the study of culture is from the beginning immersed in history. One cannot study a nation’s culture apart from the stories it tells itself about its past and its aspirations for the future.’ Same with families and other institutions, especially with ‘Abrahamic communities.’ Cobb states: ‘We urgently need stories that locate us all in one history and that history in its total natural environment. … We have become aware that our stories have been told by those who have power and we are trying to hear the other stories.’

‘Typically, a few control and exploit others to produce cultural goods, and the exploited laborers have little freedom or dignity. On the other hand, from time to time, at least in some cultures, work has been respected and laborers are full members of the society. No culture can claim to be ecological that does not reward and respect those whose labor enables it to flourish.’ Food is important to culture ‘What is eaten, and how it is produced distributed and eaten,’ as is ‘how we build homes and cities’. Furthermore, ‘The realization of mortality shapes reflection on meaning. An ecological civilization will affirm death as well as life. … Cultures differ in the degree to which they encourage, or even allow, criticism. … Ecological civilization requires drastic criticism of current activities but will always call for self-criticism as well.’ This section also emphasized the need for art and pop culture to reflect ecological civilization and positive social change in music, movies, tv, sport, etc. (54)

Section 12 – Transformative power of Art

‘All building and eating and technology and story-telling are culturally important, but people learned long ago that these could be done better and more effectively. This better and more effective doing is what we call art. … Story telling is an art. … The power of art to modify or challenge or transform a culture both at the popular level and among the elite means that those who now seek a deep cultural transformation need to give it special attention and emphasis.’ From protest music to religious rituals and pop art and high culture, ‘opening up for us new ways of seeing the world. …The artists also offer us the most powerful instruments for effecting an actual change of consciousness.’ (58)

Introductory Courses to Whitehead’s Philosophy

I decided to do one of the introductory courses offered simultaneously to the sessions within the above sections, in order to deepen my understanding of Whitehead. These were taught by two leading Whiteheadians Arran Gare and Robert Mesle. Given the length of this blog post I’ll save that for another time…

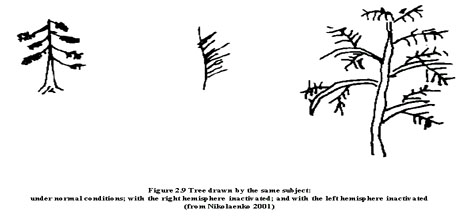

Recent work in neuroscience, for example on stroke survivors and using new technologies that light up when different parts of the brain are being used, are illuminating this in exciting ways.

Recent work in neuroscience, for example on stroke survivors and using new technologies that light up when different parts of the brain are being used, are illuminating this in exciting ways. First it is important to make clear, as McGilchrist does again and again that the idea that the left hemisphere gives us reason and language, while the right hemisphere gives us images and emotion is false: we need both hemispheres in order to deal with these things, from reason and emotions to interpreting language and images. McGilchrist writes: ‘every identifiable human activity is actually served at some level by both hemispheres’ (1).

First it is important to make clear, as McGilchrist does again and again that the idea that the left hemisphere gives us reason and language, while the right hemisphere gives us images and emotion is false: we need both hemispheres in order to deal with these things, from reason and emotions to interpreting language and images. McGilchrist writes: ‘every identifiable human activity is actually served at some level by both hemispheres’ (1). In this RSA 21st Century Enlightenment animation to McG’s TED Talk you can get a good introduction to these ideas:

In this RSA 21st Century Enlightenment animation to McG’s TED Talk you can get a good introduction to these ideas:

My latest academic publication – on the work of my favourite philosopher of all time: Alan Watts, and how his “dramatic model of the universe” can contribute to peace 🙂

My latest academic publication – on the work of my favourite philosopher of all time: Alan Watts, and how his “dramatic model of the universe” can contribute to peace 🙂![By J Zapell [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://julietbennett.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/1024px-FallPando02-494x327.jpg)

This book shares the same essential message of countless books, articles and lectures that followed: you are not only what is inside your “bag of skin”, you are what is outside of it too. To kick off the new year, let me explain what this means and how it relates to happiness…

This book shares the same essential message of countless books, articles and lectures that followed: you are not only what is inside your “bag of skin”, you are what is outside of it too. To kick off the new year, let me explain what this means and how it relates to happiness…