It is a common misinterpretation of the Theory of Evolution to think that there is a clear line between species—this is what Richard Dawkins calls “The Tyranny of the Discontinuous Mind.” If we are connected in time to all species, then are we not also connected to the big bang? In fact, within such a continuity, can we not define our selves as the Big Bang, expressing itself in different forms? Let’s explore Dawkins’ tyranny along with my all time favourite, Alan Watts.

In The Ancestor’s Tale, and further elaborated on in an online article called “The Tyranny of the Discontinuous Mind,” Dawkins points out that there was no “first Homo sapien.”[1] Every generation of our ancestors ‘belonged to the same species as its parents and its children.’ If we travelled back in time to meet our ‘200 million great grandfathers’, we would eat him ‘with sauce tartare and a slice of lemon. He was a fish.’[2]

Dawkins emphasises, ‘Evolutionary change is gradual: there never was such a line, never a line between any species and its evolutionary precursor.’[3] There is an unbroken lineage going back through history that connects us with every one of our ancestors. At every step along the way, one generation of our ancestor could breed with another of its being from numbers of generations before and after.

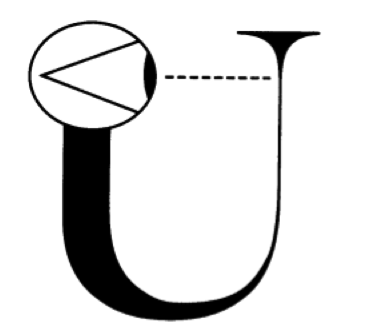

Dawkins illustrates this with the tale of the herring gull and the lesser black-backed gull in the Arctic Circle.

[youtube]http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CEtnyx0Yo9I[/youtube]

The herring gull and the lesser black-backed gull are two different species, named the Larus argentatus and Larus fuscus, that do not breed with each other. Dawkins refers to these gulls as ‘ring species’ as ‘at every stage around the ring, the birds are sufficiently similar to their immediate neighbours in the ring to interbreed with them.’[4] Yet when the ‘ends of the continuum are reached’ in Europe, these birds live side by side but do not interbreed with each other. Dawkins calls explains that ring species like the gulls ‘are only showing us in the spatial dimension something that must always happen in the time dimension.’[5]

The point of this tale is to demonstrate that what we perceive to be discontinuities between species is due to the limitations of our mind, existing inside this particular period of time. Mapping evolution through time is much like mapping the transition from the herring gull to the lesser black-backed gull across Europe. What does this mean? It means that ultimately humans are connected to all other species and micro-organisms tracing back to the Big Bang.

Let me illustrate the significance of this with a Wattsian metaphor.

Imagine that a bottle of black ink thrown on a large white wall. Taking ‘for the sake of argument’ that the Big Bang was the way it happened, the black ink represents a primordial explosion, that ‘flung all the galaxies out into space’. The ink splatters outward. It is very dense in the middle and has squiggly bits on the outer edges. It is common for us to think ourselves only a speck of ink on the outer edge of this 14 billion-year process, but we are not: we are the whole thing. Watts explains:

‘If you think that you are only inside your skin, you define yourself as one very complicated little curlicue, way out on the edge of that explosion. Way out in space, and way out in time. Billions of years ago, you were a big bang, but now you’re a complicated human being. And then we cut ourselves off, and don’t feel that we’re still the big bang. But you are. Depends how you define yourself.’ [6]

In this view, ‘You are the big bang, the original force of the universe, coming on as whoever you are.’ [7]

We have forgone the ‘proper self-respect’ that comes with recognizing that ‘I, the individual organism, am a structure of such fabulous ingenuity that it calls the whole universe into being.’[8]

Watts provides a vision of what it means to experience life as a “panentheist”. Panentheism (all-in-God) defines “God” as a cosmic process that we are inside and part of, rather than as something separate like the old notion of a supernatural man judging us from the sky. This insight is found within most religions, but it can get lost in some nit-picking “authorities” interpretation of doctrines, generally connected with power-seeking institutions.

This can shift the way you see and care for yourself, for the other people, and for forms of life including your surrounding ecosystems and planet.

One can think of themselves as the curlicue, a bag of skin, cut off from everything else; or one can think of themselves as the big bang, a creative cosmic energy that is still in process—it depends on the standpoint from which one tells their story.

Life is asking itself: What is Life? [9]

[1] Richard Dawkins and Yan Wong, The Ancestor’s Tale : A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Life. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2004. and Richard Dawkins (2013, 28/1/13). “The Tyranny of the Discontinuous Mind”, Accessed: 10/03/13, http://www.richarddawkins.net/news_articles/2013/1/28/the-tyranny-of-the-discontinuous-mind#. Originally published in New Statesman, the Christmas issue for 2011, of which Dawkins was a guest Editor.

[2] Richard Dawkins, The Tyranny of the Discontinuous Mind, Accessed: 10/03/13 p. 4.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Richard Dawkins and Yan Wong, The Ancestor’s Tale : A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Life, 2004. p. 303.

[9] John Wheeler’s “Participatory Universe”, we are the self-reflexive eye that emerged within life’s story. From Paul Davies, The Mind of God. New York: Penguin books, 1992. p. 225.