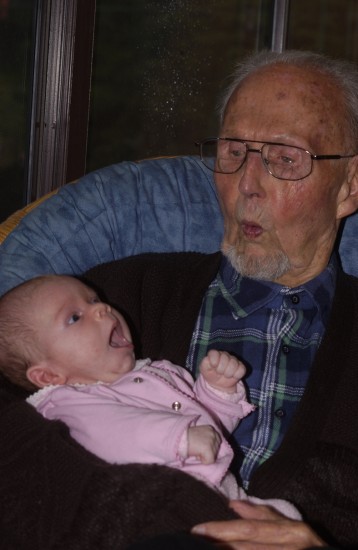

Yesterday at 5pm my Opa (that’s dutch for grandfather), passed away at the ripe old age of 93. Born 20th February 1916 in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, Willem Frederik Van Leeuwen lived a long and inspiring life. He was a wonderful, caring father and grand-father. Me and my Opa were “house-mates” (as he used to say), and he was my very good friend.

My Opa changed my life. My Masters degree is his Masters degree. My book to soon be published is his book as much as mine. I couldn’t have done either if it were not for him. The peace I shall share with the world I shall share because of my Opa. Living with him was a pivotal chapter of my life. He have opened my mind to new perspectives; he have opened my life to new opportunities. I left Vienna after I dreamt of my Opa – of me spending time at his home as he taught me to paint. Six months later I moved in, and he did just that: I learned to paint a new reality. Opa gave me a new perspective of space and time. He taught me to look beyond society’s facades, to see things for what they are. Through Opa I have come to truly appreciate the temporality of life. Life is short. Very short. We must take hold of it. Live it. Make the most of every moment. And not look back.

One hundred years is not a long time. Go back twenty of such lifetimes it was the year zero, the time where Jesus lived and died. Jesus spoke up against the Jewish dogma and Roman oppression of his time. Almost seventy years ago my Opa too protested against status quo, issuing fake identities to save lives of Jews. This took courage. This makes me proud.

When I was in my teens two thousand years seemed an ancient and irrelevant past, but from my Opa’s eyes, two thousand years is like the blink of an eye. Only fifty of his lifetimes have past since the Egyptian pyramids were built. In the big scheme of things our temporal state in the shells we currently embody, mean nothing.

My Opa used to look out at the stars, in awe of God’s universe, and appreciating the miracle of life. He wondered what other fantastical creatures exist beyond our vision but he didn’t think about it too hard. He didn’t worry about that which we cannot know. “Why think about it?” he said to me, shrugging his shoulders. Opa felt no need to define life’s magic, to humanise it, or to tell himself he knew everything about it. He didn’t question it, he didn’t judge others; he just felt it, embraced it, and played out his role in it. Opa was a man of simple faith.

Opa took pleasure in the little things: a homemade cup of coffee, a black tea, a small glass of port; a smile and a kiss on the cheek; a soccer game, a newspaper or an interesting session of Lateline. I now realise how little we need in order to live. Opa lived through wars eating rosebuds to fill his stomach. Opa left his country in order to create the best life he could for our family in Australia.

Opa has taught me to be grateful for all I have; to live for today; to live in the moment; to accept my limitations, acknowledge my weaknesses, to not let my mind or body cause me too much pain. I have learned from him that luxury is over-rated and unnecessary. He taught me to need little, and want less. Observing Opa I have come to understand that no person or thing can make us happy: happiness comes from within. Happiness begins with being content with what we have. Opa was happy with the life he lived. He was happy with the love he received. He did not want more than he was given. He accepted the jobs that came his way, he didn’t strive to have more or care about how he compared to others. He loved his children, and his grandchildren, and his wife; and he were grateful for all the love he received from us in return.

And now as he has left the physical body I knew him to be, I am reminded that there is more to life than that our individual consciousness of today. I have seen through my Opa’s death that the breathe behind life never dies; it just morphs, transforms, like caterpillars into butterflies.

Our lives are but temporal expressions of divinity. I believe, as many religions do, that our souls leave their human homes to be “reunited with God”, to be reunited with everyone they have ever loved or known, reunited through the re-absorbing of our soul into the collective soul of the universe – as we return to the oneness from which we came. No more ups and downs; no more fear, no more greed, no more suffering – a heavenly state of harmonic bliss. We are no longer separate, we become one with God; we are one with the past, present and future; we are one with the magical wonder behind our universe, the magic that is our universe and the magic beyond the universe from which we exist within.

Now I type, I can feel my Opa’s energy surrounding me. I can see my Opa’s energy in the trees, I can feel him in the wind, I can hear his heart beat in mine. I know he is with me. He will always be with me.

Opa, I want to say to you: THANK YOU.

Thank you for your part in bringing me into the world. Thank you for taking me into your home. Thank you for making me laugh. Thank you for enjoying my food. Thank you for making me interested in politics. Thank you for putting up with my mess. Thank you for sharing your views on life. Thank you for changing my life. I will cherish my memories of our time together. I will love you forever.

I will miss your bright blue eyes and your wide happy smile.

May you rest in peace, may you live for eternity.

A few years back he wrote his memoirs which some two years ago now we typed up together. I wish to share his words and his story with you today:

…

Reading about all the new findings in the digital world arriving in the market in the near future. So I thought it a good idea to put on paper how life was when I was born half way through the First World War in 1916.

Since that time, so many things have been invented which changed the way of life in many ways and I think you would be interested to know about that.

To start with my birth. As far ass I know that happened at home going into the hospital was an exception in those days and as far as my mother was concerned I must have caused her quite a bit of trouble because I have always heard her say “That was once but never again”. So that was it. I was confined to be an ‘only child.’

To start with my growing up. This happens to be in Amsterdam. I still remember the address: 20 Wetering Dwars Street in the CBD, close to the National Museum.

This is a narrow street, with 3 story home units, like terraces, on both sides. Those units were rented as owning your own place was an exception.

Actually, there were four living quarters because there was a basement half way the bottom part. To enter the more sophisticated part of the building you encountered the so called ‘stoep’ this is a concrete stag of steps to reach the front door for the three units above. To make your arrival known you had to pull the bell cord. One time for the first floor, two times for the second and so on. Then a climb up a steep timber staircase with an ‘overloop’, sort of a landing between floors

The inside of the unit consisted of a kitchen, a ‘back’ or living room, and a front room with windows. In between the two rooms was an ‘alcoof’ – a simple bedroom with inbuilt double bed on one side and my bed on the other side. There were no windows so the ventilation must have been very restricted. The front room was the so called ‘mooie kamer’ and was only used for special occasions. Further there was a ‘waranda’ balcony with an ‘ice box’. In those years there was no gas, electricity, washing machines, dryers, radio, television. Bathrooms with shower recess came many years later.

The body washing procedure was once a week on Saturday in a tub in the kitchen. The heating of water etc occurred on kerosene heater and in winter time also on a big coal and peat theater in the living room. The lighting of the unit was also by kerosene lamps. The washing of linen underwear etc was done by hand in a tub. Food was kept in the so called ice box on the balcony. Bars of ice were delivered once a week in the Summer months.

Although life was primitive in comparison with today’s, we were still satisfied.

I started my education in the elementary school close by, but as there was a small canal at the end of our street, my mother always took me to school as she was afraid I would fall in the ‘dirty’ water.

Schools in those days did not have play grounds so all my ‘playing’ was done in the street.

Most of my school years were very uneventful. Reading books etc. was my main way of life.

I remember my parents having card evenings with a Jewish family from across the street. They had a daughter of my age and we were confined to the alcoof. This was quite fun. The family disappeared out of my life and I never found out what happened.

There were also friends who had a tobacco shop and a private library. I spent many hours reading over there.

I must have been about 8 years old when we moved to a better environment.

Again a unit on the third floor with a ‘view’! Over looking a canal with a lot of ship movements. Barges pulled by tugs and at the other side on industrial area of mainly timber yards. The school was close by but again no playgrounds so life was mainly spent at home and occasional staying with my grandparents in Haarlem.

This brings me to tell about my parents.

My father was born in Amsterdam as far as I can remember, in 1894. He was a builder by trade. He must have been a pretty good one as I remember him building a large school complex later on he built houses on his own accord which had to be sold in time to be able to finance the next project. Often there were financial difficulties which affected the atmosphere at home.

He came from a fairly large family of several brothers and sisters with kids. There was however a little contact so I don’t remember much of it.

His father, I never met my grandmother, lived on his own in the Huidenkoper street in Amsterdam. He was retired from a function in the Royal Palace in Amsterdam.

His living quarters were filled with beautiful antiques, which would have been worth a fortune if they had stayed in the family. Still he was not very family friendly and I believe he preferred to see us going than coming. Consequently I did not see much of him.

It was a different matter with my mother’s parents. They lived in Haarlem in Amsterdam street near the Amsterdam Gate. The family name was ‘Van Vreeden’. My grandfather was a retired carriage painter with the Dutch railways. My mother had one brother ‘Oom (uncle) Cor’ who being a bank manager, was the family’s ‘financial pillar’.

In my younger years for some reason or another I often stayed with my grandparents and I remember making long walks with my Opa. I think because Oma got fed up with us and kicked us out.

My mother was, I think, a seamstress, because I saw her sitting behind a treadle sewing machine for long hours. When my grandmother past away, there was great emotion in the family of the question “What to do with Opa…?”

Fortunately my father was building two houses in Haarlem in the Kemp Straat, and he had difficulty in selling one of them (most probably because they were built next to a large cooperative bakery.) The solution of the above question was solved, with the financial influences of Oom Cor, that we moved to Haarlem and Opa was living with us. In comparison with the home units in Amsterdam, this was a considerable improvement. It was a two story house with plenty of rooms, a small back yard with a shed, and even a bathroom. I must have been about 12 years old because I went straight to High school. After leaving school in 1934, my first employment was with Hotel Royal in Haarlem as a receptionist and in the administration.

In 1936 I went for my number in the army with the horse driven field artillery in Utrecht.

After discharge in 1937, I worked with Travel Bureau Lissone Lindeman.

For August 1939 I was called up again for military service in Socstduinen near Utrechet.

This lasted till May 14 when Holland surrendered to the Germans. Luckily we did not fire one shot because we would not have stood a chance with material dated back from before the First World War. The whole exercise lasted a couple of days and ended promptly with the air raids of Rotterdam.

We were discharged and from July 1940 I worked with the Rationing Service in Haarlem. I started a chief in the National Registration Certificate Department. Because of the many Rassias it was important that next to your ‘Stamcard’ you could prove that your work was too important to be missed, preventing you from being sent to labour camps in Germany. So apart from the administration of the registry, we were also occupied with creating of fake Declaration of Requirements for the underground and Jews.

It may be of interest for you to give sort of a survey of life during the German occupation. The first two years we were living with coupons etc. Life did not change too much. We were able to organize Balls, Theatre performances, Youth Clubs etc.

However when the Germans started to persecute the Jews, things became ugly.

We had a group of about thirty boys and girls, with whom we managed to organise bicycle holidays or house evenings. However we had to become more and more careful. You always had to watch your back to prevent from being picked up from the street and sent to Germany.

Life with coupons became gradually more and more difficult as in many occasions the goods in the coupons were simply not available. Especially the last half year became very hard. We had a curfew from 8pm to 7am. The southern part of Holland beneath the big rivers was liberated but the part above the rivers was left to keep on its own. As there was practically no import of food and the Germans confiscated anything edible. Hunger started to lift its nasty head. People went to barter valuables for edibles. Walking with improvised carts to farmers in order to be able to live.

Many did not survive those journeys or got their valuable food confiscated when they returned to their house in the city. On many occasions we hat to resort to eat grounded tulip bulbs as so called cookies. All in all the last year was very nasty.

It was only after the Allies managed to defeat the Germans near Arnhem that life became gradually better. After 1946 I worked in different positions in the Ministry for Economic Control.

My last position was an inspector with an Economist fund for the small goods trade.

After the war the detail trade was practically at bottom level. Stocks had disappeared and ‘new starts’ had not occurred for at least three years.

The retail trade needed an urgent lift and the government was prepared to guarantee loans with the bank for people to finance a new business. For this purpose an organization was created to investigate the viability of the business concerned. I became and inspector with this organization and travelled all over Holland to report about the applicants’ capability and family – determining whether the business could be expected to be viable to pay off the loan within a certain time limit. This report went to a board within this organization and the decision of the application was granted or refused. As a side line I was a manager with an association called Infantex, of about 50 specialist shopkeepers of articles in baby goods. I organized about three market days in Krasnapolsky in Amsterdam and at the Royal Hotel in Urtrecht. There would be about thirty stalls in where the manufacturers would show their newest creations. All this lasted until May 1961 when we departed to Australia.

Coming back to my life in Haarlem. I met your mother on Saturday 29th July 1944, in a swimming pool called Stoop. As she had no ‘transport’, I took her home on the back of my bike and from there on we stayed together.

Her father Jacob Bas had his trade as a plumber and a shop in the Atjeh Street in Haarlem.

Her mother’s family name was Platenga and both came from farmer’s families in West Friesland. Your mothers family name was Agatha Jacoba Bas, born 19th January 1920. She could not get along very well with her father and her mother was always the protective part.

Anyway, we got engaged on 24th December 1944, and on 14th June 1945 we married in Haarlem as one of the first after the war.

The wedding day started very curious as there were no hire cars available. We had to hire horse drawn carriages. They also were very sparse. Anyway we managed to hire two. One would collect the parents from their homes, and one for us.

On the big day, however, only one turned up. The other had been in an accident. You can imagine the consternation to get us all to the Civic Centre. It was decided that the parents were collected first and we last. So we waited in the Atjeh street home. Because of the distances of the addresses, it took quite a while. Finally the carriage turned up. Very late, and to make up time we went in gallop to the City Centrum. The carriage swayed from left to right, and the public looked in amazement to the race. I must say it did not bother us in the least and we had great fun. We still made barely on time.

I had managed to rent a whole house in the Pegasus street in Haarlem, which in those days must have been the envy of many in the neighborhood. Later we moved to the Jan Gyzen-kade in Haarlem Noord, and from there we bought with the help of Opa Bas, a house in Velzen Wustelaan and after a few years we sold the house and bought a house in Ede Arthur Van Schendelaan. This was more central in Holland and more suitable for my work with the financial institution.

This was the last house in Holland till our departure to Australia.

Although I had a very interesting job, we decided that in view of the increases in population in Holland, being new about the size of Tasmania, with a population the same as Australia, the future for the children was better in Australia.

14 May 1961. We boarded the Orange, and 19 June 1961, we arrived in Sydney. We were sponsored by Fien an Piet Voorderhake. They had rented a house on Pittwater road in Collaroy, for 10 pound a week. At that time there was a sort-of economic depression.

Although I had studied English correspondence in Holland, it was not easy to understand Australian English.

Fortunately I met Jan Van Beest, who was chief clerk in Prince Alfred Hospital. He introduced me to the accountant and I was appointed as a clerk in the Administration.

In 1963, Jan Van Beest became an accountant in the new built Mona Vale Hospital. He asked me to come with him. I accepted and became chief clerk and accountant when Jan Van Beest departed to New Zealand.

In January 1974, I transferred to the budget department of Royal North Shore Hospital, where I stayed to my retirement in January 1982.

…

This is where they finish. It is crazy to imagine all of this happening before I was even born. My Opa had enjoyed twenty-seven years of retirement, twenty-seven years of a simple peaceful life in his modest home in Frenchs Forest.

With age comes wisdom. I learned a lot from my wise old Opa, I hope you have been able to learn something too. God bless.

“Love Is”

“Love Is”