Rather than debating “Is there are God?” shouldn’t it first be clarified “what exactly one is referring to by this word “God”? Can Panentheism provide a new slant on the God debate between New Atheists and Fundamentalist Christians?

I am having a mini thesis crisis – overwhelmed by wanting to say too much on too many things, referring to too many theorists, so I thought I’d share part of it with you and see if that helps. Some of the questions I ask myself:

- Does “God” need to be understood as supernatural king-like deity that is an all-powerful separate being intervening from outside?

- Must the theory of evolution and the scientific worldview need to bring us to the conclusion that “we are flukes” and life is rather meaningless?

- Might the worldview of eastern religions, process philosophy, panentheist theology, spiritual ecology etc. more conducive to peace with justice (i.e. a sustainable global social and ecological well-being for humans now and future)?

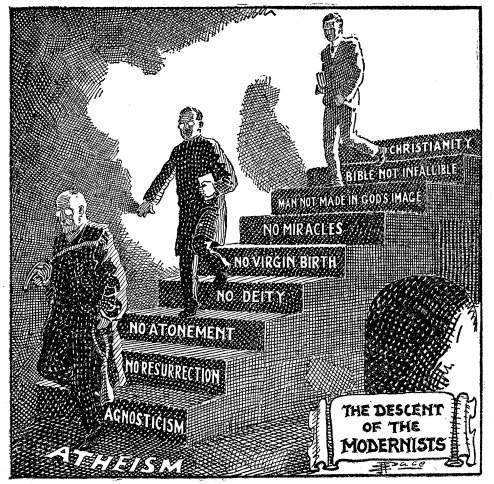

Given the supernatural understandings of God came from a people who thought earth was flat, and angels carried the sun and moon around the heavens, maybe it’s time to revisit old metaphors, and the worldviews that resulted from their rejection…

Based on a talk by Alan Watts (of course), let me (try to) explain what I’m talking about.

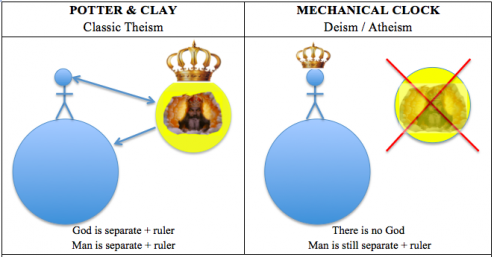

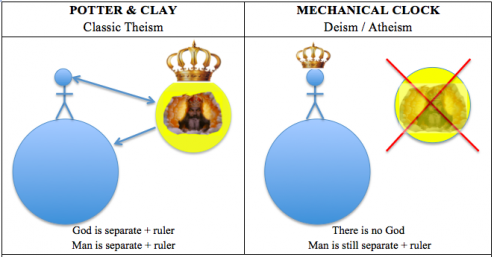

Two worldviews dominate western culture:

1. POTTER & CLAY: Based on the creation story in Genesis: earth is an artifact, created by a separate king-like supernatural God (in yellow), who deems man (who is also separate from nature) its steward, yet dominates over it.

2. MECHANICAL CLOCK: Based on the rejection of the Genesis story: the universe is a machine that started with a Big Bang: life is random, meaningless, a bunch of balls on a billiard table. Yet the assumptions from the first model remain: man stole the king’s crown, but continues to be separate from nature, continuing to dominate, divide and conquer.

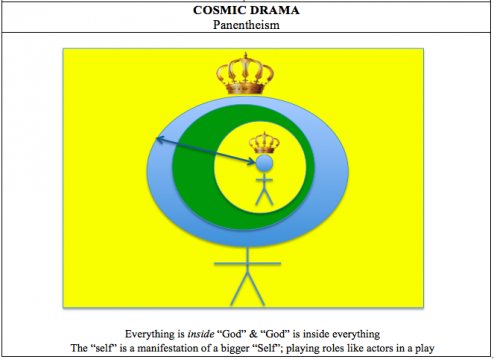

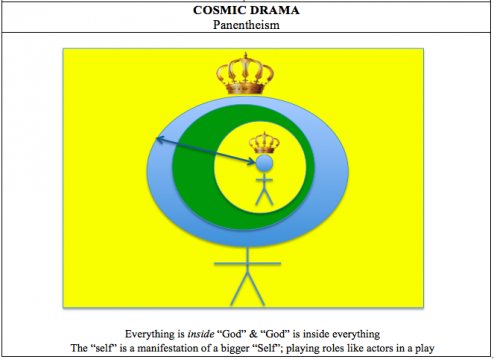

Is there another way to tell the story?

3. COSMIC DRAMA: In the “dramatic” model of the universe, life is seen as a game, a dance, a play, with God manifesting Itself in acting different roles. In this sense “you” are God, and everything else. This idea can be seen in Eastern philosophies, in deep ecology, spiritual versions of western religions and process theology or panentheism (all is God).

Panentheism is the idea that everything (pan) is inside (en) a macrocosmic entity some refer to as “God” (theism).

Panentheism is considered by many scholars to be a natural, rational and ecological alternative to the polarized classic theism and atheism.[1]

While the term is not widely recognized, the philosophical ideas proposed by panentheism underlie many religious and scientific understandings of life. It is inherent to most Hindu and Buddhist philosophy, Neopaganism, Indigenous worldviews, and the more liberal Christian, Islam, and Judaic theologies.[2]

The widely quoted Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church define panentheism as:

“The belief that the Being of God includes and penetrates the whole universe, so that every part of it exists in Him, but (as against Pantheism) that His Being is more than, and is not exhausted by, the universe.”[3]

Watts says:

“You have seen that the universe is at root a magical illusion and a fabulous game, and that there is no separate “you” to get something out of it, as if life were a bank to be robbed. The only real “you” is the one that comes and goes, manifests and withdraws itself eternally in and as every conscious being. For “you” is the universe looking at itself from billions of points of view, points that come and go so that the vision is forever new.” [1]

For me, positing your “self” as part of a bigger “Self”, as you are a temporal expression of God (as is everyone else), is an exciting story that decreases feelings of separateness and alienation, fear of death and provides an impetus for Care of the Other.

I want to know if using different metaphors and developing process understandings of God might lead to something more meaningful than the frustrating debates like between Dawkins and Cardinal Pell? Clearly these people are speaking different languages!

I want to know if a “dramatic” worldview can affect one’s actions to play a more active role in bringing about a society of peace with justice:

- Does understanding the “other” as your self—including the planet and other life forms—increase your care for other people and the environment?

- Does such a narrative increase your sense of purpose, feeling of wholeness, help come to embrace uncertainty and life’s adventure?

I realise panentheism doesn’t immediately bring about peace with justice, i.e. I realize one cannot say “because Japan is Buddhist (which could be seen as panentheism) and because India is Hindu (which could also be seen as panentheism) they are more peaceful and just then western societies” – not at all…. Maybe that’s why I feel lost. Then I add my narrative theory into the mix, and various field texts, and I feel dizzy….

I am pretty sure it is my panentheist/dramatic worldview that inspires such care and purpose in me, but I’m not sure it’s of value to anyone else…

Thoughts?

References:

[1] Eg. Birch, Charles (1999). Biology and the Riddle of Life. Sydney: UNSW Press. Griffin, David Ray (2001). Reenchantment without Supernaturalism : A Process Philosophy of Religion. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, Tucker and Grim. (1994). Worldviews and Ecology: Religion, Philosophy, and the Environment. New York: Orbis Books.

[2] Cooper mentions the works of Martin Buber (Judaism), Muhammed Iqbal (Islam), Sarvepalli Radhakrishman (Hinduism), Alan Watts and Masao Abe (Zen Buddhism), and Starhawk (Wiccan Neopaganism), among others. For example see: Johnston, Mark (2009). Saving God : Religion after Idolatry. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Borg, Marcus J. (2003). The Heart of Christianity: Rediscovering a Life of Faith. New York: HarperCollins. Smith, Huston (1991). The World’s Religions : Our Great Wisdom Traditions. [San Francisco]: HarperSanFrancisco. Rinpoche, Sogyal (1992). The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying. Sydney: Random House Australia (Pty) Ltd. Stockton, Eugene (1995). The Aboriginal Gift : Spirituality for a Nation. Alexandria, N.S.W.: Millennium Books.

[3] Clayton, Philip and Arthur Peacocke, Eds. (2004). In Whom We Live and Move and Have Our Being: Panentheistic Reflections on God’s Presence in a Scientific World. Cambridge: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. Inner sleeve.

[4] Watts The Book : On the Taboo against Knowing Who You Are. p. 118.

‘Extensive studies of colour perception over several decades have made it clear that there are no colours in the external world, independent of the process of perception.’

‘Extensive studies of colour perception over several decades have made it clear that there are no colours in the external world, independent of the process of perception.’